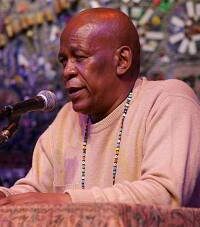

Mtutuzeli Matshoba

Mtutuzeli Matshoba was born in Soweto in 1950 and six years later began school as one the first of the Bantu education generation at a Salvation Army school in Orlando East. He attended secondary school in Lovedale in the Eastern Cape and in Vryheid in the then Natal, before being expelled from Fort Hare University in 1976 for what he admits was general insubordination. Matshoba wrote protest literature as one of the founding members of Raven Press and was also a contributor to the frequently banned Staff Rider Magazine.

In 1978, Ravan Press published his collection of short stories Call Me Not A Man. This landmark and strident collection addressed urban black and migrant worker experience after the 1976 uprisings. Matshoba also appeared in anthologies like Forced Landing and To Kill A Man’s Pride and, in 1980, won the English Academy Pringle Award in the Creative Writing category.

His short stories eventually attracted the attention of film makers, which resulted in him moving into scriptwriting. In a long and distinguished career Matshoba has been involved in the creation and writing of famous television productions such as Soweto, The History, Yizo Yizo, Stokvel, Scoop Scoombie, and Zero Tolerance. He graduated to feature film with the much acclaimed comedy Chikin Biznis, which won Best Film in FESPACO in Burkina Faso. He has also been involved in polishing the scripts for Red Dust and, more recently, Jerusalema. In 2014, Matshoba was a judge in the Twenty in 20 project, a “Twenty Years of Freedom initiative whose aim is to identify the best South African short fiction published in English during the past two decades of democracy”.

Teaching screenplay writing through his “Script to Screen in Indigenous Languages” project has revived Matshoba’s prose writing passion. He comments: “there is an unbreakable link between storytelling and the modern medium of film”. He is currently working on a graphic novel series that will chronicle historical legends of South Africa during the period of anti-colonial resistance. Its intention is to encourage interest and respect for history and indigenous languages among young readers and learners.

An extract from Call me not a man

By dodging, lying, resisting where it is possible, bolting when I’m already concerned, parting with invaluable money, sometimes calling my sisters into the game to get amorous with my captors, allowing myself to be slapped on the mouth in front of my womenfolk and getting sworn at with my mother’s private part, that component of me which is man has died countless times in one lifetime. Only a shell of me remains to tell you of the other man’s plight, which is in fact my own. For what is suffered by another man in view of my eyes is suffered also by me.

The grief he knows is a grief that I know. Out of the same bitter cup do we drink. To the same chain gang don we belong. Friday has always been their chosen day to go plundering, although nowadays they come only occasionally, maybe once in a month. Perhaps they have found better pastures elsewhere, where they their pray is more predictable than at Mzimhlophe, the place which has seen the tragic demise of three of their accomplices who had taken the game a bit too far entering the hostel on the northern side of our location and fleecing the people right in the midst of their disgusting labour camps. (1978:18)

Bibliography

1978. Call Me Not A Man. Johannesburg: Ravan Press. 1979. Seeds of War. Johannesburg: Ravan Press.