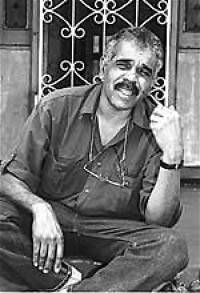

Kessie Govender

Kessie Govender (1942 – 2002) was born in Durban. His grandfather Veeraswami Govender came to South Africa from Poolioor in South India as an indentured labourer. On gaining his freedom he bought land in Cato Manor and started a market garden. Govender’s father, Mariemuthoo, was a bricklayer, and when Govender left school at the end of Grade 10, he became one too.

He was introduced to the theatre by his cousin Ronnie Govender. By the early 1960s, theatre in South Africa meant mostly white theatre staging classics such as Shakespeare and bedroom farces.

He was introduced to the theatre by his cousin Ronnie Govender. By the early 1960s, theatre in South Africa meant mostly white theatre staging classics such as Shakespeare and bedroom farces.

It bore no relation to the lives of most South Africans, it didn’t reflect indigenous language or humour, and it had nothing to say about the issues of the day. Few, if any, resources went into theatre that was not white. To remedy this, Ronnie Govender and a small group of others brought the eminent Indian director Krishna Shah to South Africa to run a clinic. The result was the Shah Theatre Academy, which ran workshops to encourage and train young actors and writers to fill the gap in the local drama scene. Among the first to attend was Kessie. The fact that the academy existed to help create more enlightened drama did not mean that it didn’t have its fair share of backbiting and snobbery, and Govender was looked at askance as an untutored upstart. When Ronnie chose him to fill the lead in his play Beyond Calvary, there was no end to the hissing. “How can you put this monkey on stage?” demanded one furious speech and drama graduate who had coveted the role. Kessie, never short of confidence in his abilities or his cause, went storming ahead regardless, and drew the first of many accolades from the local press.

In the 1970s he began writing and directing as well, to fill the void of suitable pieces on issues he felt needed addressing. “So much was starting to come to the boil, politically, and there was so little available that expressed the situation, so I got down to it and began writing and staging my own plays,” he recalled in an interview. His first – and one of his few real commercial successes – was Stable Expense, after which he named his Stable Theatre.

Money was definitely not one of Govender’s driving passions, and he made so little of it that those who knew him never ceased to wonder how he managed to keep body and soul together, let alone support a wife (whose teacher’s salary was invaluable) and two children.

Despite this, he was always ready to help some struggling artist get a bite to eat or pay for transport. And, no matter how pressed he was, he always made time to read scripts brought to him by young hopefuls. A number of would-be actors and writers now working in mainstream theatre owe their start to Govender. He died of a heart attack in 2002 and is survived by his wife, Jayshree, and two children. In 2013 Stable Theatre honoured Govender by presenting a revival of his first play, Stablexpense, in 2013.

(Adapted from Chris Barron’s “Working class hero of theatre for the people” Sunday Times. 3 Feb 2002)

Selected Work

from Working Class Hero – a stage play in two acts Period – 1976. About three months before the Soweto uprising. Location – A building site in a suburb close to Durban.

People in the play

Frank: Unskilled builders’ labourer (African)

Jits: Bricklayers’ chargehand (Indian)

Siva: Artisan bricklayer (Indian)

Anand: Third year law student at University of Durban Westville (Siva’s brother)

Grievenstien: Building Industry Labour inspector (White)

Stage or performing area to depict a building site. Scattered about are builders’ scaffoldings, a medium sized ladder, a doorframe, motar boards, bricks in piles and packed in stacks. A few empty cement bags lie crumbled. The action and props are permitted to spill outside the allowed conventional working space. Entrances and exits of characters are decided to suit chosen venues. The play is a continuous performance without scene changes, there is a short tea break for the characters on stage, during which time the audience is free to do as it pleases. Stage props are listed on the last page of this book.

Act One

The curtains are up before the audience enters the theatre. (preferably there should be no curtains) The house lights are low. The stage or performing area is to create the impression that the place has not yet been cleared and made ready for a performance.. This is to stimulate the audience to feel as curious intruders rather than detatched spectators. There is no set, and as there are no conventional chairs, actors would have to improvise their comfort needs. An incomplete raked brickwork corner of a building stands starkly out of place.

Words from the song ‘Working Class Hero’ are heard as the houselights are lowered. Performance lights to indicate early morning. In the diffused light FRANK wheels in barrow of bricks and tips them randomly. Turning his barrow he exits. Reloads and returns. He stops close to the pile of bricks but does not empty the barrow. Leaving the barrow, he walks to an already packed stack of bricks, on top of which is a partly eaten unsliced half loaf of brown bread and a chipped mug of tea. Picking up the bread he takes a bite pulls the cement bag over the paint container, seats himself on it, continues eating and sipping tea. At the end of the song, lights fade in gradually to normal visibility.

( Enter Jits. He is carrying a kit bag in one hand and a newspaper in the other. )

FRANK : (as Jits walks past him.) Yebo Baas.

JITS Ya( barely acknowledging Frank. ) ( walks to a stack of bricks) What time do you start work’?

FRANK : Dala Baas, long time, must be sometimes apas six.

JITS : Then what you still sitting on your arse for? ( removes tea flask from kit bag. )

FRANK : Awa ngidila iblekfasti Jits.

JITS : Is Temba coming today?

FRANK : Angazi. I dunno.He was sick Friday

JITS : Ya I know that story. Every Friday he’s sick, and every Monday he’s absent. Right then, you better mix the daka.( pours tea into cup. )

FRANK : Ow xovile gaate. That time I’m getting up I’m mixing the daka everything.

JITS : Then come on, move it with the bricks man. What you waiting for? ( reaches into pocket for cigarettes. )

FRANK : ( empties barrow, exits. ) (sounds of bricks clattering into barrow is heard offstage.)

JITS : (it’s his last cigarette, he squashes the packet and flings it away, looks towards Frank and calls.) Frank, ( receives no response, shouts.) Hey Frank, you bastard.

FRANK : ( above the sound of bricks thrown into barrow. ) Yebo Baas.

JITS : Get me a packet of cigarettes.

FRANK : ( offstage) In’ Baas’?

JITS : Lo ugwayi man, you bloody shit. You got cement in your ears what?

FRANK : (enters with barrow loads of bricks. stops his barrow and removes bricks by hand, after packing some of them into a stack, he walks to Jits, collects money, looks down at the money in his hand.) Ow Jits borrow me one rand please.

JITS : What one rand? One rand, one rand, one rand. What do you think I am’? Your father or something? Do you know how much you owe me?

FRANK : Ow siza Jits, I want to tenga some inyama.

JITS : Well use your own money, you got paid last week.

FRANK : Ow Jits, siza bo, hambisile mall ekhaya.

JITS What’s that?

FRANK : I’m sending the mall to the farm. I’m never going to the farm, musbe three months. I’m sending the money for my wife and my children.

JITS : Hey shit man, that’s your wife and your children, and I hope you’re not blaming me for any of them.

FRANK : ( walks towards barrow, takes a few steps then turns around as if a new though has struck him, walks back to Jits. ) Hey Jits, shiya zonke le zinto leaving it all that one rand everything and giving it me only one twenty cents.

JITS : Alright, take it from the rand.

FRANK : Ow Baba, wanyisiza kakhulu ( goes down on one knee in mock gratitude. )

JITS : You just give me back my money, that’s all.

FRANK : Not to worley Jits. I’m giving it back your money. ( resumes packing bricks. )

JITS Hey, how much you taking there now?

FRANK : Twenty cents.

JITS : Didn’t you say that you were going to buy meat? What meat you going to buy for twenty cents? You don’t take fifty cents and say you only took twenty cents. You hear?

FRANK : You mus’nt think I’m a lobber Jits. I’m getting it a inyama for the twenty cents. I’m going there by the butcher, I’m saying there by him, I ley wena, the baas he say lie want the amadogbones for twenty cents. When I say that, lie say, Which baas? I say the baas for the building. Ow when I say that, he pick it all the nice, nice amathambo and he gimme lot, lot inyama. ( pause, scratches his head in puzzlement.) Ow, hey Jits, I don’t know why he give the baas’s dog, lot, lot ama bones, goto that time I say that it is for me, he give it me leetle bit amabones, no inyama nothing.

JITS : Maybe he doesn’t like you.

FRANK : How he can saying he don’t like it me, He not knowing me nothing (pause) (as if it suddenly dawns on him) Noo. He know that the baas is a Mulungu, he get flightened. But me? I’m clever me, anything I want it, I say the Baas he want it, the baas he want it.

JITS : Alright, alright, leave all that and get my cigarettes.

FRANK : Awright

Bibliography

1974. Stable Expense. [s.n.]

1975. Tramp –you, Tramp – me. [s.n.]

1975. Ravanan. [s.n.]

1976. Working Class Hero. [s.n.]

1977. The Decision. [s.n.]

1978. The Shack. [s.n.]

1979. Ka-goos. [s.n.]

1981. On the Fence. [s.n.]

1984. Black Skies. [s.n.]

1998. Underground. [s.n.]

1991. Stablexpense. [s.n.]

1994. God Made Mosquitoes Too. [s.n.]

1995/6. Alternative Action. [s.n.]

1996. Herstory. [s.n.]