Jan van Tonder

.Jan Christiaan van Tonder was born on 29 August 1954 and grew up in Durban. He has a degree in psychology and criminology. He started writing in 1979 while he was working as a warder at the Point prison in Durban. The story was published and was selected as Huisgenoot‘s short story of the month. Besides prison guard he has also worked as ticket inspector, stoker, restaurant manager, training official, journalist, painter and writer. He was court reporter and arts editor at the Transvaler and was then appointed as chief sub-editor at the SABC in Pretoria.

He has been nominated for an Artes Award for radio reporting. He has been living in Oudtshoorn for a number of years.He made his debut in 1983 with the novella Wit vis. It was followed by a collection of short stories, Aandenking vir ’n vry man, which, just like his succeeding novella, Is Sagie, was a runner-up for the ATKV Prose Prize. His fourth book, Die kind, received the ATKV Prose Prize in 1990 and the FAK Prize for easy reading in 1991.

Roepman, the movie, was released in 2011 in Afrikaans with English subtitles to much critical acclaim.

Website:

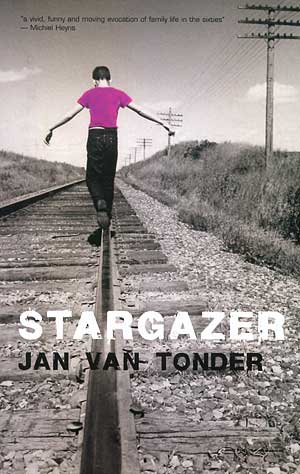

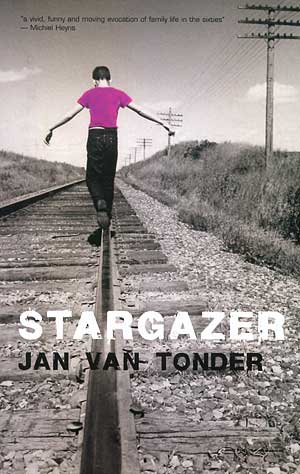

Extract from Stargazer:

If you walked from our place up to where the Lighthouse Road met Bluff Road at the top, and then carried on along Bluff, up the hill, right up to the top where it began to descend towards Wentworth, you came to a water tower. It was an enormous thing – you could see it clearly from below. That was where our water came from, along a thick pipe that passed under the road, and from there thinner pipes brought the water to the houses. If you left the hose on the ground and you opened the tap wide, a jet of water spurted out that made the hose swing from side to side, standing up and falling down like a thing about to strike.

If you walked from our place up to where the Lighthouse Road met Bluff Road at the top, and then carried on along Bluff, up the hill, right up to the top where it began to descend towards Wentworth, you came to a water tower. It was an enormous thing – you could see it clearly from below. That was where our water came from, along a thick pipe that passed under the road, and from there thinner pipes brought the water to the houses. If you left the hose on the ground and you opened the tap wide, a jet of water spurted out that made the hose swing from side to side, standing up and falling down like a thing about to strike.

We would jump over it and duck and try not to get wet, but often the hose would twist suddenly and then you’d be hit by an icy blast. When Ma saw this, she’d shut off the water. “It’s only people who don’t do their own washing who’ll play in the water like this,” she’d remark.

In the evenings after supper Gladys fetched hot water for her bath. There was only cold water in her kaya. First she fetched her food and stacked dirty dishes in the oven to wash them the next morning. Otherwise her day was too long, Ma said. By the time she came for her bath water, it was dark outside. One evening I set a trap for her. As she came walking back to her kaya with the bucket balanced on her head, I opened the tap. Shhhh! said the hose. Gladys stopped in her tracks. All of a sudden the water spurted and the hose began to swing to and fro. Gladys screamed and dropped the bucket. Before I could shut off the water, Ma was standing in the back door.

I got a hiding, of course. Ma was furious. “There could have been boiling water in that bucket – what then?”

“She never fetches boiling water, Ma.”

“Never mind. She’s a grown-up. If you want to scare someone, try someone your own size.”

I didn’t say so to Ma, but no one I knew – not Joepie or Hein or anyone else – would’ve got such a good fright as Gladys did that evening.

Bibliography

Prose

1983 Wit vis, Perskor 1984 Aandenking vir ’n vry man, HAUM 1987 Is Sagie, HAUM 1989 Die kind, HAUM/Kagiso 2004 Roepman, Human & Rousseau 1998 The Little Karoo / Die Klein Karoo (with Lanz von Horsten), Human & Rousseau

Translations

Roepman (2004) : Stargazer (2006) Die kind (1989) : Ongenagama, the Child with No Name

Movies

Roepman (2011)

Extract from Stargazer:

If you walked from our place up to where the Lighthouse Road met Bluff Road at the top, and then carried on along Bluff, up the hill, right up to the top where it began to descend towards Wentworth, you came to a water tower. It was an enormous thing – you could see it clearly from below. That was where our water came from, along a thick pipe that passed under the road, and from there thinner pipes brought the water to the houses. If you left the hose on the ground and you opened the tap wide, a jet of water spurted out that made the hose swing from side to side, standing up and falling down like a thing about to strike.

If you walked from our place up to where the Lighthouse Road met Bluff Road at the top, and then carried on along Bluff, up the hill, right up to the top where it began to descend towards Wentworth, you came to a water tower. It was an enormous thing – you could see it clearly from below. That was where our water came from, along a thick pipe that passed under the road, and from there thinner pipes brought the water to the houses. If you left the hose on the ground and you opened the tap wide, a jet of water spurted out that made the hose swing from side to side, standing up and falling down like a thing about to strike.

We would jump over it and duck and try not to get wet, but often the hose would twist suddenly and then you’d be hit by an icy blast. When Ma saw this, she’d shut off the water. “It’s only people who don’t do their own washing who’ll play in the water like this,” she’d remark.

In the evenings after supper Gladys fetched hot water for her bath. There was only cold water in her kaya. First she fetched her food and stacked dirty dishes in the oven to wash them the next morning. Otherwise her day was too long, Ma said. By the time she came for her bath water, it was dark outside. One evening I set a trap for her. As she came walking back to her kaya with the bucket balanced on her head, I opened the tap. Shhhh! said the hose. Gladys stopped in her tracks. All of a sudden the water spurted and the hose began to swing to and fro. Gladys screamed and dropped the bucket. Before I could shut off the water, Ma was standing in the back door.

I got a hiding, of course. Ma was furious. “There could have been boiling water in that bucket – what then?”

“She never fetches boiling water, Ma.”

“Never mind. She’s a grown-up. If you want to scare someone, try someone your own size.”

I didn’t say so to Ma, but no one I knew – not Joepie or Hein or anyone else – would’ve got such a good fright as Gladys did that evening.

Bibliography

Prose

1983 Wit vis, Perskor 1984 Aandenking vir ’n vry man, HAUM 1987 Is Sagie, HAUM 1989 Die kind, HAUM/Kagiso 2004 Roepman, Human & Rousseau 1998 The Little Karoo / Die Klein Karoo (with Lanz von Horsten), Human & Rousseau

Translations

Roepman (2004) : Stargazer (2006) Die kind (1989) : Ongenagama, the Child with No Name

Movies

Roepman (2011)