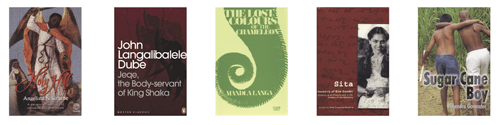

Mandla Langa (1950 – ) was born in Durban, grew up in KwaMashu township, and studied at the University of Fort Hare Since returning to South Africa from exile he has worked in broadcasting while continuing to write. His published work includes Tenderness of Blood (1987), A Rainbow on a Paper Sky (1989), The Naked Song and Other Stories (1997) and The Memory of Stones (2000). His latest novel, The Lost Colours of the Chameleon, was published in 2008 to critical acclaim, winning the African section of the 2008 Commonwealth Prize.

Angelina Ntombizanele Sithebe was born and raised in Soweto, but completed her high school education at Inanda Seminary. At the end of 2004, she wrote her debut novel Holy Hill. Set in Durban and Zululand, the novel deals with African ancestral beliefs in a modern society. During 2006 and 2007 five of Sithebe’s short stories, under the title A Target Life Series were published by Amazon.com.

Gandhi Family

Mohandas ‘Mahatma’ Gandhi arrived in Durban in1893. During his 21 years in South Africa he engaged in peaceful struggle for equality and justice for all before the law. In 1903 he started the newspaper Indian Opinion, a paper his son Manilal stressed was for “the political, moral and social upliftment of the Indian community”, and a year later he established the Phoenix Settlement in Durban.

Manilal Mohandas Gandhi (1892 -1956) was the second son of Gandhi and was active in his father’s Satyagraha movement. Although born in India, he worked for almost five decades as the editor of the Indian Opinion in Durban, with, as his daughter Sita remembers, every thing being done by “hand as we had no electricity”.

Like his father, Manilal also spent time in jail for protesting unjust laws enforced by the British colonial government. In 1927, Manilal married Sushila Mashruwala, and had two daughters, Sita and Ela, and one son, Arun. Manilal’s granddaughter, Uma Dhupelia-Mesthrie, published a biography of Manilal titled Gandhi’s Prisoner? The Life of Gandhi’s Son Manilal (2004).

Sita Gandhi (1928 – 1999) was Mahatma Gandhi’s granddaughter. She wrote a memoir of her childhood in Phoenix Settlement, entitled Sita – Memoirs of Sita Gandhi (2003). These memoirs shed light on what it meant to be related to Gandhi. Sita shows that being Gandhi’s granddaughter was not easy. Her book not only describes growing up at the Phoenix Settlement in the shadow of a strong man, but also discusses being an Indian woman in South Africa.

Mewa Ramgobin (1932 – ) was born in Inanda. He was the President of the Natal Indian Congress (NIC), founded by Gandhi in 1894, and married Gandhi’s granddaughter, Ela. Ramgobin established the Gandhi museum and library, organised the Annual Gandhi Lecture and educated people from different race groups on Gandhian thought. In 1986 he published his novel Waiting to Live and in 2009 published his second book Prisms of Light.

John Langalibalele Dube (1871-1946) was born in the Inanda district and was the author of the first novel to have been written in isiZulu, U-Jeqe, Insila ka Tshaka (1930) with an English translation, Jeqe, the Body-servant of King Shaka, in 1951. Dube, a founding member of the South African Native National Council (later the ANC), established the newspaper Ilanga lase Natal in 1903. Writing in an Appendix to Jeqe, Dube states, “It has been my lot in life to further the cause of my people, to labour for their enlightenment and advancement, both in temporal and in spiritual matters. I live to serve them, however poor my service may be, and however disheartening at times the work may be.”

Herbert I. E. Dhlomo (1903 – 1956), the younger brother of R.R.R. Dhlomo, was born in Siyama Village near Pietermaritzburg. In the Thirties he was assistant editor of Ilanga lase Natal, where he worked closely with Dube. Dhlomo wrote the first drama published in English by a black South African author. Titled The Girl Who Killed to Save (1936), it is based on an episode in Xhosa history: the cattle- killing tragedy of 1857. Dhlomo later wrote poetry praising Dube and the Ohlange Institute.

Ellen Kuzwayo (1914 – 2006) was a women’s rights activist and writer. In 1937 she graduated from a teacher’s training course at Lovedale College when, she writes ,“I received an invitation from Inanda Seminary near Durban to teach there, which I accepted.” She was president of the African National Congress Youth League in the 1960s, and in 1994 was elected to the first post-apartheid South African Parliament. Her autobiography Call Me Woman (1985) won the CNA Book Prize.

Rubendra Govender (1966 – ) was born and grew up in Inanda. His first novel, Sugar Cane Boy (2008), is loosely based on his life experiences of the social, cultural and political way of life which was unique to the sugar cane farms during the Apartheid era.

Creative INK is a project that aims to use literature as a regeneration tool. Its members have produced, Creative INK Anthology (2008), a book of poetry and prose in English and isiZulu.

History

Inanda , which means ‘Pleasant Place’ in isiZulu, is situated about 25km inland from Durban and forms part of the eThekwini Municipality. In the early 1900s, several wealthier African families, including the Dubes and Gumedes, bought farmland in Inanda. Many Indian agriculturalists also bought land here. Govender describes them in his novel Sugar Cane Boy:

Many of these families were second and third generation descendants of the indentured labourers who were shipped into the then Natal Colony from 1860 onwards to work on the sugar estates. After serving their periods of indenture, some of the more enterprising families bought their own small-holdings.

Until the 1920s, these landowners were able to make a decent living from their crops. However, they steadily found that discrimination was undermining their long-term viability. In the 1930s, the entire area of private landholding in Inanda was designated an African area in terms of unfolding segregationist legislation. Until then, Indian and African communities had co-existed in the area. Manilal Gandhi writes:

My father was a very well loved man and when he took his morning walks he would pass Mr [Rev] Dube’s Ohlange Institute and pop in and have a chat with him. Then he would pass the Shembe Colony and the first Mr Shembe was a very good friend.

In the late 1950s the apartheid government introduced tight controls over entry to urban areas, building new townships all around Durban. Access to housing became dependent on jobs. The largest and most important informal shanty town in Durban, Cato Manor, was destroyed and some residents were moved to KwaMashu. Ramgobin’s protagonists in Waiting to Live, Elias and Lucy, have “the use of a two-roomed brick dwelling with an asbestos roof in Kwa Mashu, at a rent set down by the Durban city fathers.” Those with no jobs were to leave the city altogether. They, however, moved further out to places like Inanda.

In the 1980s, Inanda changed from being a relatively quiet shanty town to an extremely dense settlement characterised by high levels of unemployment. Langa describes a fictional settlement in The Lost Colours of the Chameleon, which bears some similarities to KwaMashu:

People lived cheek by jowl in unimaginable squalor. The buildings towered over a mingle-mangle of meat and vegetable market stalls where disembowelled fruit littered the ground and rose, together with offal and the stained feathers of plucked poultry, to a mountain of garbage that was topped by a carpet of green flies that buzzed with fulfilment

From 1985 onwards, Inanda was caught up in a spiral of violence. First, the remaining Indian residents of the area were chased out, then there was politically motivated violence between the ANC and IFP particularly in lower Inanda. Since 1994, the situation has calmed down dramatically. Today Inanda, Ntuzuma and KwaMashu (INK) collectively form part of an ambitious urban regeneration programme, initiated by the South African government.

Places To Visit

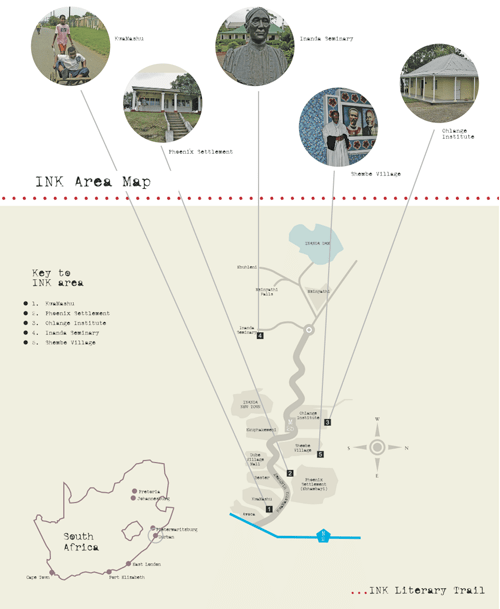

1. KwaMashu

The township of KwaMashu was formed by the apartheid state to house the mass resettlement of Africans from Cato Manner during 1958-65. It is the largest of 3 townships in the area (Inanda and Ntuzuma are more rural with a lower population density. Many of INK’s residents are unemployed and the area has been associated with violence and crime in the past. Despite these challenges, within the township a lively performing arts scene thrives. Muzi Ngema writes in Creative INK Anthology of his experience of the township:

I am from KwaMashu, 27 kilometres from Durban. Anyway, KwaMashu is now part of the Durban Metro. New dispensation, new demarcations! I have survived punches and stitches and KwaMashu has survived orchestrated wars but we are still us.

2. The Phoenix Settlement

The Phoenix Settlement is situated on the north-western edge of Inanda. Sita Gandhi writes , “my grandfather’s farm … was fifteen miles away from the city. Over 100 acres of land was called Phoenix Settlement. It was the most beautiful piece of land, untouched by the then racial laws.” However, life was not easy for the Gandhis, with “no proper roads to go into the city. If it rained there was mud all over and the little bridges would be over-run by the water and it was impossible to go anywhere”.

Throughout its long history, the Settlement has played an important role promoting justice, peace and equality. It was also, however, a family home for the Gandhis, as Sita writes:

We had a beautiful garden surrounding the house and in the middle of it was a very tall coconut tree which was planted by my grandfather. … We had a beautiful white horse and often sat on him. We also had five or six cows and calves and dogs and cats. My father loved animals and so I grew up loving them too.

In 1985, during the Inanda Riots, the Settlement was badly damaged. Writing about a similar riot (Cato Manor, 1949), Manilal said, “Intemperate word and action will not help and must not be thought of. We must think and probe deeply into the cause of this dreadful affair and try to work for the removal of these causes. … We must befriend the Africans, not cut away from them, and strive unitedly for the common interest of all”.

After the riots the Settlement was overtaken by about 8 000 informal settlers. Since then, the Phoenix Settlement Trust has faithfully restored the buildings and gardens to their original state and established an interpretation centre and museum. Sushila Gandhi (the wife of Manilal and mother of Sita) sees the “institution as a memorial to Gandhiji,” and writes that it “will always be a place of pilgrimage, for those who seek inspiration to better their lives and gain a little from the great men who have passed on.” The area is presently known as Bhambayi (Bombay).

3. Ohlange Institute

Ohlange Institute was founded by the John Dube in 1901. Dube’s guiding principle in life was to ‘hasten slowly’. This became the basis of the education policy he introduced at Ohlange, insisting that students be thoroughly equipped for their future careers. Dube was inspired in his educational vision by a visit to the Tuskegee Institute of Alabama where he developed a friendship with Booker T Washington. However, the Bantu Education Act of 1953 impacted hugely on Ohlange School resulting in the decline of a proud school that was once described as a ‘citadel of light’. HIE Dhlomo’s poem, written in 1912, captures the school’s vision:

Above the Ohlange heights?There hover ever glorious lights?They glow, they gleam, they quiver?Ever, ever, ever,?As a flowing river?From the mighty hand of God.

When Nelson Mandela cast his vote in the first democratic elections in 1994, he chose to do so at the Ohlange Institute.

4. Inanda Seminary

Inanda Seminary was founded by the American Board of Missions in 1869 with Mary Kelly Edwards as its first principal. It became the first secondary school exclusively for African girls in southern Africa. Its reputation grew rapidly and the school soon attracted students from across the continent. Kuzwayo describes the community that existed around the Seminary in Call Me Woman:

Just outside Inanda Seminary stood a small village of the black community. The majority of the inhabitants were congregants of the American Board Mission Church which had built the girls’ school. The Rev. Gumede, the pastor of the local church, lived with his family in the village (and his daughters) were by all standards as good as any from the cities and towns of South Africa.

It was not until the 1970s that the government dismissed the ABM missionaries and teaching staff, refusing to renew their residence permits. The United Congregational Church of Southern Africa (UCCSA) attempted to uphold quality education at Inanda but by 1997 the Seminary was on the verge of closure. However, past pupils have rallied together and set up a trust, which has restored the school and now manages it. In Holy Hill, Sithebe describes a school outing from her fictional seminary, probably based on similar outings from Inanda Seminary:

Once a year the girls were taken down to Durban in a Pullman bus for cultural activities and for the beach. Before the day their heads were shaved of all hair so they would be neat and smart. Any sign of beauty was obliterated, so as not to tempt the fast, weak city men.

Isaiah Shembe

Of cultural interest to many is the Shembe village. In 1911, Isaiah Shembe founded the iBandla lamaNazaretha (Nazareth Baptist Church), a religious movement rooted in Zulu tradition. Shortly afterward he acquired a farm that became his holy city of Ekuphakameni (the church later split forming an alternative congregation at Ebuhleni) and established an annual pilgrimage to the sacred mountain of Nhlangakazi.