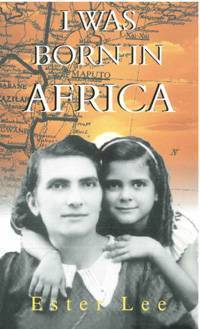

Ester Lee

Ester Lee (1936-) born in Lourenço Marques, now Maputo, Mozambique. After completing high school, as there was then no university in the country, she spent a year learning English, to enroll at the University of Natal, Durban to study Architecture. With the death of her father in 1962 she returned to Mozambique and worked in the family business ‘Catoja Saldanha’. She soon returned to Durban to marry, raise her family, and make Durban her home. She later started to write short stories which were published by umSinsi Press. Her first book was based on the life of Dona Ermelinda, her mother, was written during the filming of the documentary The Double life of Dona Ermelinda, a documentary produced by her son Aldo, for French television. The word ‘Double’ worried Ester: she was one. She has not stopped writing since that time.

She later started to write short stories which were published by umSinsi Press. Her first book was based on the life of Dona Ermelinda, her mother, was written during the filming of the documentary The Double life of Dona Ermelinda, a documentary produced by her son Aldo, for French television. The word ‘Double’ worried Ester: she was one. She has not stopped writing since that time.

She lives in a Victorian house of books, authors, and sometimes films, in Durban. On her identity, Ester says, “I am a Mozambican with a Portuguese identity, that lives in South Africa. I belong to and love all three: Mozambique from birth and happy memories of childhood; Portugal because they speak the language that my blood understands, and South Africa for its people.”

Extract from I was born in Africa.

The Nightmare

He looked at her carefully. Her dirty dress hung on her like from an old coat-hanger-the dress she always wore, from the time when she had flesh on her. Her thin pale face was still smooth at her age. Her haunted eyes were whitened by cataracts, her thin steel grey hair was plaited like a rat’s tail down her back, over her thin hunched shoulders. She had brown false teeth. But there was still some beauty on her. And that unusual strength.

He looked at her carefully. Her dirty dress hung on her like from an old coat-hanger-the dress she always wore, from the time when she had flesh on her. Her thin pale face was still smooth at her age. Her haunted eyes were whitened by cataracts, her thin steel grey hair was plaited like a rat’s tail down her back, over her thin hunched shoulders. She had brown false teeth. But there was still some beauty on her. And that unusual strength.

‘My last wish,’ she said to him, is to be buried alive’.

She spoke as if from the dead. But she was sitting at the table across from him in the dining room.

The bright July sun came pouring in. The sunlight spread into the house, scattering the cockroaches, spiders and other creatures who lived in fear of light.

A plastic table cover, which had been there for several years, was now stuck to the once beautiful wood of the dining room table. The small pale yellow roses printed on it were still faintly visible amongst the bits left behind from past meals, when they had food to eat.

He sat opposite her, trying to calm his persistent hunger.

‘I want to die with the assurance that I shall be laid beneath the ground, and the only way I can be sure of this, is to ask you to bury me alive; you are the only one who knows where I want to be buried.’

He remained calm. ’I promise’ he said.

They had been together for some years and he was used to agreeing with her. He knew that her time had come. She was tired, she wanted to go.

‘I am begging you again. Can you do it?’

‘I will, and my hand will not even shake,’ he answered her.

‘I know that my end has come, because last night I could smell roses,’ she told him.

She trusted him. She went upstairs to her room, bent double, one hand holding on to her knee, the other sliding along the wall for balance, taking one step at a time.

He did not move or paid any attention to her. He just sat there staring at the plastic table cover.

The sun was now disappearing, so he must have been sitting there for a long time. Then he too started to move upstairs.

Her voice came to him clear from her body. ‘Do not forget to bury me alive. You have promised.’

He waited outside the bedroom a long time before going in. She had fallen asleep. He half woke her. She was so tired, but she still said, in her sleep, ‘Don’t forget, before they lay me in the family sarcophagus, next to my husband, who has been there for thirty years. Be charitable to me and do it. Bury me alive.’

With the utmost calm, he promised once again to do it.

He rolled over to the edge of the bed and tried to go to sleep, but he could not do so until dawn when the bugs left him with the arrival of the morning sun, it filtered through what used to be curtains and were now only dirty uneven strips of fabric with no definite colour, not strong enough to stop the sunlight from coming in. The sun filled the room with its brightness.

Something woke him up. He turned to look at her. She was foaming at the mouth, her eyes open and wild, and she was trying to tell him, ‘do it’.

On the bed next to her, on his hands and knees, he stared back at her. He was surprised to find that when rich white people were dying they looked so much like the poor blacks.

‘I am sorry,’ he whispered, ‘for not doing it. It is too late now’.

He could smell roses stronger than the stench from the street.

Bibliography

1996. Mãe. Durban: umSinsi Press.

1999. I was born in Africa. London: Minerva Press.