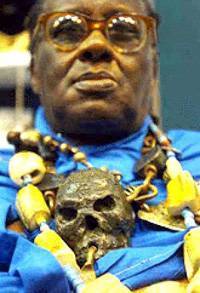

Credo Mutwa

Vusamazulu Credo Mutwa (1921 – 2020 ) was born in Natal. His father was a former Catholic catechist from the Embo district near Inanda. His mother was the descendant of a long line of Zulu medicine-men and custodians of tribal lore and customs. His parents parted shortly after Vusamazulu’s birth, because his mother refused to convert to Christianity. Mutwa was educated by his maternal grandfather, a medicine-man, and carrying the bags for him, the boy learned some of the older man’s secrets. In 1928 Vusamazulu was taken to the Transvaal by his father. They lived on a farm near Potchefstroom, where his father was a labourer.

In 1928 Vusamazulu was taken to the Transvaal by his father. They lived on a farm near Potchefstroom, where his father was a labourer.

After twenty years of working on different farms the father found employment in one of the Johannesburg mines as a carpenter. Mutwa himself found employment in 1954 in a curio shop in Johannesburg. When he visited his mother and grandfather in Zululand after thirty years of absence, he renounced Christianity at their command, and underwent the ceremony of purification, in order to begin training as a medicine-man. He also prepared himself to assume the post of custodian of tribal lore and customs in the event of his grandfather’s death. Mutwa has written African tales which have their roots in oral, traditional Zulu culture. Two well known collections of these stories are Indaba My Children (1966) and My People: writings of a Zulu Witchdoctor (1969).

In 2015, a documentary based on his life story, The Voice of Africa: Credo Vusamazulu Mutwa, was screened at the Native American Film & Video Festival. In 2016, a musical production (Song of Nongoma), which was based on his writings, premiered at the South African State Theatre.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vusamazulu_Credo_Mutwa

Selected Work

From Indaba, My Children (1964)

The beautiful queen of the Wakambi, the peerless Marimba, was walking through the forest with her handmaidens on her way to the riverside to bathe her body in the cool waters. Birds sang in the trees overhead and the forest was heavy with the scent of thousands of flowering shrubs. Myriads of butterflies and colourful insects were fluttering in clouds of white, blue and brown among the wild flowers and the buzzing song of nyoshi, the bee, was clearly heard in the blinding sunlight. Timid hares galloped through the long grass and the cooing voice of le-iba, the turtle dove, added yet more enchantment to an already enchanting day.

The sky was the purest of blue, Only a few clouds were to be seen in the eternal expanse of the heavens and those were as soft as wool and as delicate as the body of a Sun-maiden.

As the queen went through the forest, her great-eyes were as alive as moon crystal. From the enchanting woodland scene she drank in inspiration as the grateful grass drinks the morning dew. Where the ordinary man sees only the trees,’ she saw them in their dignity and superb beauty; and where the ordinary man hears only the rustling of the breeze through the branches of the trees, and the senseless twittering of the numerous birds, she heard the soul-stirring verses of the Song of Creation. She was not very far from the river when she saw a number of young boys gathered together above something that lay in the tall grass, The boys were talking and gesticulating excitedly and were all patting one amongst them on the back in obvious congratulation. Their voices floated through the scented air into the keen ears of Marimba and, as one might expect from this great woman, she left her retinue and went to investigate.

What she saw there filled her with anger and disgust, and tears sprang unbidden into her eyes. One of these boys had invented a particularly vicious and cowardly kind of snare. With which to catch young antelopes. He had tried it out and it had worked all too well. Lying on the ground With a cruel noose around her lifeless neck was a young steenbuck ewe which had fallen a victim of this fiendish trap, and the poor animal had only a few days to go before it produced young. “Which of you sons of night-howling, splay-footed, green-bellied hyenas invented this thing?” demanded Marimba hotly. The boys made no reply. They just stared at their dusty feet in very frightened silence. Two of them wetted their loinskins at the same time, much to the amusement of the royal handmaidens.

“I asked you a question, you mud-wallowing tadpoles! ” cried Marimba. At last one of them said in a voice that was hardly a whisper: “I . . . I did, Oh Great One.” “You did, did you?” cried Marimba in a burst of ecstatic fury. “Now indeed, you are going to suffer for your deed!”

“Mercy please, Oh Great One,” whispered the boy. “Marimba has no mercy for bloodthirsty little idiots of your kind,” said the angry queen coldly. “Breathe into the nostrils of that animal and bring it back to life.” The astonished followers of Marimba saw the boy lift the head of the dead buck and actually try to breathe life back into it. There was a gale of feminine laughter which the angry chieftainess quelled with a look of cold fury in her glittering eyes. A deep respectful silence settled upon the group of watching maidservants while the boy, with sweating face and inflated cheeks, and a heart that was almost stopping with cold fear, huffed and puffed in vain to revive the dead animal.

“That animal had better come back to life, Oh little vermin,” said the princess cruelly. “If it does not you will soon wish that you had never been born.” The badly frightened boy tried his best. He tried everything he could while the queen watched him coldly and impassively, and the handmaidens watched with broad smiles on their faces.

“Why”, said Marimba at long last, “it seems to me as if you find it easier to kill an animal than to bring it back to life!’

Bibliography

1964. Indaba My Children. London: Kahn and Averill.

1966. Africa Is My Witness. Johannesburg: Blue Crane Books.

1969. My People: writings of a Zulu Witchdoctor. Penguin Books.

1981. uNosilimela. In R. M. Kavanagh (ed), South African People’s Plays. London: Heinemann.

1987. Let not my Country Die. United Publishers International.

1996. Song of the Stars: The Lore of a Zulu Shaman. Barrytown Limited.

1996. Isilwane: The Animal. Johannesburg: Struik Publishers.

1997. Usiko: Tales from Africa’s Treasure Trove. Johannesburg: Telkom.

2001. Vusamazulu Credo Mutwa: Zulu High Sansui. Ringing Rocks Press in association with Leet’s Island Books.

2003. Zulu Shaman: Dreams, Prophecies, and Mysteries. Destiny Books.

2007. Mutwa, C, Rathele, V. Woman of Four Paths – The Strange Story of a Black Woman in South Africa. Sunpath Llc

In 2015, a documentary based on his life story, The Voice of Africa: Credo Vusamazulu Mutwa, was screened at the Native American Film & Video Festival. In 2016, a musical production (Song of Nongoma), which was based on his writings, premiered at the South African State Theatre.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vusamazulu_Credo_Mutwa

Selected Work

From Indaba, My Children (1964)

The beautiful queen of the Wakambi, the peerless Marimba, was walking through the forest with her handmaidens on her way to the riverside to bathe her body in the cool waters. Birds sang in the trees overhead and the forest was heavy with the scent of thousands of flowering shrubs. Myriads of butterflies and colourful insects were fluttering in clouds of white, blue and brown among the wild flowers and the buzzing song of nyoshi, the bee, was clearly heard in the blinding sunlight. Timid hares galloped through the long grass and the cooing voice of le-iba, the turtle dove, added yet more enchantment to an already enchanting day.

The sky was the purest of blue, Only a few clouds were to be seen in the eternal expanse of the heavens and those were as soft as wool and as delicate as the body of a Sun-maiden.

As the queen went through the forest, her great-eyes were as alive as moon crystal. From the enchanting woodland scene she drank in inspiration as the grateful grass drinks the morning dew. Where the ordinary man sees only the trees,’ she saw them in their dignity and superb beauty; and where the ordinary man hears only the rustling of the breeze through the branches of the trees, and the senseless twittering of the numerous birds, she heard the soul-stirring verses of the Song of Creation. She was not very far from the river when she saw a number of young boys gathered together above something that lay in the tall grass, The boys were talking and gesticulating excitedly and were all patting one amongst them on the back in obvious congratulation. Their voices floated through the scented air into the keen ears of Marimba and, as one might expect from this great woman, she left her retinue and went to investigate.

What she saw there filled her with anger and disgust, and tears sprang unbidden into her eyes. One of these boys had invented a particularly vicious and cowardly kind of snare. With which to catch young antelopes. He had tried it out and it had worked all too well. Lying on the ground With a cruel noose around her lifeless neck was a young steenbuck ewe which had fallen a victim of this fiendish trap, and the poor animal had only a few days to go before it produced young. “Which of you sons of night-howling, splay-footed, green-bellied hyenas invented this thing?” demanded Marimba hotly. The boys made no reply. They just stared at their dusty feet in very frightened silence. Two of them wetted their loinskins at the same time, much to the amusement of the royal handmaidens.

“I asked you a question, you mud-wallowing tadpoles! ” cried Marimba. At last one of them said in a voice that was hardly a whisper: “I . . . I did, Oh Great One.” “You did, did you?” cried Marimba in a burst of ecstatic fury. “Now indeed, you are going to suffer for your deed!”

“Mercy please, Oh Great One,” whispered the boy. “Marimba has no mercy for bloodthirsty little idiots of your kind,” said the angry queen coldly. “Breathe into the nostrils of that animal and bring it back to life.” The astonished followers of Marimba saw the boy lift the head of the dead buck and actually try to breathe life back into it. There was a gale of feminine laughter which the angry chieftainess quelled with a look of cold fury in her glittering eyes. A deep respectful silence settled upon the group of watching maidservants while the boy, with sweating face and inflated cheeks, and a heart that was almost stopping with cold fear, huffed and puffed in vain to revive the dead animal.

“That animal had better come back to life, Oh little vermin,” said the princess cruelly. “If it does not you will soon wish that you had never been born.” The badly frightened boy tried his best. He tried everything he could while the queen watched him coldly and impassively, and the handmaidens watched with broad smiles on their faces.

“Why”, said Marimba at long last, “it seems to me as if you find it easier to kill an animal than to bring it back to life!’

Bibliography

1964. Indaba My Children. London: Kahn and Averill.

1966. Africa Is My Witness. Johannesburg: Blue Crane Books.

1969. My People: writings of a Zulu Witchdoctor. Penguin Books.

1981. uNosilimela. In R. M. Kavanagh (ed), South African People’s Plays. London: Heinemann.

1987. Let not my Country Die. United Publishers International.

1996. Song of the Stars: The Lore of a Zulu Shaman. Barrytown Limited.

1996. Isilwane: The Animal. Johannesburg: Struik Publishers.

1997. Usiko: Tales from Africa’s Treasure Trove. Johannesburg: Telkom.

2001. Vusamazulu Credo Mutwa: Zulu High Sansui. Ringing Rocks Press in association with Leet’s Island Books.

2003. Zulu Shaman: Dreams, Prophecies, and Mysteries. Destiny Books.

2007. Mutwa, C, Rathele, V. Woman of Four Paths – The Strange Story of a Black Woman in South Africa. Sunpath Llc