Ronnie Govender (1934 – ) was born in Cato Manor and has strong feelings about this community, as is evident in most of his 13 plays and his collection of stories, At the Edge and Other Cato Manor Stories, for which he received the Commonwealth Writers’ Prize. As a protest against bourgeois theatre he formed the Shah Theatre Academy to foster indigenous theatre. The Lahnee’s Pleasure, one of South Africa’s longest running plays, and At the Edge, both received critical and commercial acclaim. In 2000, Ronnie Govender was awarded a Medal by the English Academy of South Africa for his contribution to English literature. Govender published Song of the Atman, part of which is set in Cato Manor, in 2006.

Lewis Nkosi (1936 – ) worked for many years as a magazine editor and broadcast journalist in Durban (Ilanga lase Natal), Johannesburg (Drum), London (The New African), and the U.S. (NET). He is the author of several collections of essays; two plays, The Rhythm of Violence (1964) and The Black Psychiatrist (2001); and the novels Mating Birds (1986), Underground People (2002), and Mandela's Ego (2006). The protagonist in Mating Birds lived in Cato Manor. His career as Professor of Literature has included positions at Universities in Africa (Zambia), the USA (Wyoming, California (Irvine)), and Europe (Warsaw). Now resident in Switzerland, Lewis Nkosi frequently travels to literary conferences as an invited guest.

Gladman Ngubo, also known by the name Mvukuzane, was born in Cato Manor. Whilst working in Durban he became a trade unionist where his talent as a writer and a praise poet was discovered when he recited his work at trade union rallies. In 1987 he joined the Congress of South African Writers (COSAW). In 1988 he was elected to serve in COSAW’s Provincial Executive structure in KwaZulu-Natal where he earned respect because of his passion for developing writers from previously disadvantaged communities. He has published a number of Zulu-language novels including Yekanini Ukuzenza!

Kessie Govender (1942 – 2002) family was from Cato Manor. His grandfather Veeraswami Govender came to South Africa from Poolioor in South India as an indentured labourer. On gaining his freedom he bought land in Cato Manor and started a market garden. Govender's father, Mariemuthoo, was a bricklayer, and when Govender left school at the end of Grade 10, he became one too. He was introduced to the theatre by his cousin Ronnie Govender and went on to act, write and direct plays. His first was Stable Expense, after which he named his Stable Theatre but Working Class Hero became his most well known.

Mi S'dumo Hlatshwayo (1951 – ) grew up in a working-class household in Cato Manor. His family's poverty caused him to leave school by Grade 9 and search for a job. It was the Dunlop strike of 1984 that triggered him to cultural action. After hearing Qabula perform his izimbongo of FOSATU, he realised that one did not need to be traditionally educated to write poetry. He composed “A Black Mamba Rises”, his most well known poem, to praise the Dunlop workers' struggle. He joined Qabula and others to form the Durban Workers' Cultural Local. Hlatshwayo has since composed more poems, and written and directed plays.

Kenneth Bhengu, known as the sage of Ndwendwe, lived in Cato Manor where he set three of his novels, all concerned with shady characters living there. He also worked as gardener in Morningside, the setting for another of his novels. Bhengu is a prolific Zulu-language novelist and has published 18 novels and novellas, many of them with either history or legend as background.

History of Cato Manor

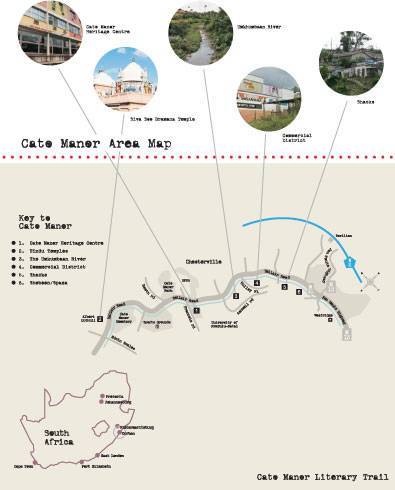

Situated about ten kilometers from the centre of Durban, Cato Manor is an area rich in cultural and political heritage. Durban’s first mayor, George Christopher Cato, gave the area its name. Cato Manor’s first residents, the Indian market gardeners to whom Cato sold the land, later leased plots to African families prohibited from owning land themselves. The vibrant, Afro-Indian culture that came into being from this shared space became a trademark of the area. Its Zulu residents knew the warren of shacks, shebeens and shops that grew into Cato Manor as Umkumbaan – named after the stream on whose banks the shantytown sat. Cato Manor survived and thrived for many years as a rough-hewn community in direct contradiction to the Apartheid government’s policy of racial segregation.

Famous residents included musician Sipho Gumede, politician Jacob Zuma, activist Florence Mkhize, businessman Prince Sifiso Zulu, Drum journalist Nat Nakasa and trade unionist George W. Champion who saw Cato Manor as a “place where Durban natives (Africans) could breathe the air of freedom.” So legendary was its reputation that novelist Alan Paton wrote a play Umkhumbane set in Cato Manor.

1949 Race Riots

Despite the daily contact between Indian and African residents, who lived in close proximity to each other, racial tensions did exist. Charges of exorbitant rent where often leveled against Indian landlords by their African tenants who had to cope with terrible living conditions, characterised by intense overcrowding. In Working Class Hero, playwright Kessie Govender explores the Indian exploitation of the African community in Cato Manor.

Ronnie Govender in At the edge and other Cato Manor Stories describes the 1949 riots, which were sparked off by an incident in Grey Street where an “Indian stallholder had caught an African boy stealing and had punished him.” Africans began attacking Indian shops, businesses and residents. The riot quickly escalated into a race-war with some “white people … stirring up the trouble.” The situation deteriorated with African mobs roaming the streets of Cato Manor attacking Indian residents on sight. That evening the “arson, looting and raping increased. The smell of petrol and paraffin were in the air and the night sky was lit up by soaring flames. … Indians with cars were fleeing.” It took two days for the authorities to get the situation under control. By this stage many shops and homes had been destroyed, 137 people killed and thousands more injured.

1959 Beerhall Riots

In the 1950s, rural Zulus moving to Durban for work sought out Cato Manor as a convenient place of residence. The area quickly grew to accommodate this influx with 6000 shacks – housing around 50 000 people – erected in a matter of years. To earn money, African women brewed and sold beer to male residents. Nkosi elaborates in Mating Birds, in “Cato Manor, African women lived mainly by brewing an illicit concoction called skokiaan, which was often laced with methylated spirit to give it an extra kick. This dangerous and mind-destroying brew was then served daily to black workers, who, evening after evening, as soon as they left work, flocked to their favourite shebeens, where they thirstily imbibed the stuff”. The Durban municipality encountered problems controlling illegal brewing, which was in competition to their municipal beer halls. Constant pass and liquor raids conducted by the police in Cato Manor agitated residents creating a potentially explosive situation.

By the mid-1950s, the area had become a political hotbed, with Chief Albert Luthuli garnering support for the African National Congress by linking Cato Manor’s problems to the greater struggle against Apartheid. Mi S'dumo Hlatshwayo, a child of Cato Manor and influenced by its politics, later went on to write struggle poetry – collected in Black Mamba Rising – that mobilized workers against the government. Commenting on the classification of the African in Apartheid South Africa, Hlatshwayo wrote:

Today you’re called a Bantu,

Tomorrow you're called a Communist

Sometimes you're called a Native.

Today again you're called a foreigner,

Today again you're called a Terrorist

This random classification extended to place where the government would conveniently reclassify areas to suit their needs.

Durban’s white city-council felt threatened by this large community of politicized Africans and Indians on their doorstep and in 1959 Cato Manor was declared a white zone under The Group Areas Act (1950). Ronnie Govender wrote, “It was right here in black-and-white. The impossible had happened. In the name of community development, in the name of group rights and group protection, in the name of western civilization, Cato Manor was declared a white area. All the families that had lived there for generations now had to move out of their homes, away from their own pieces of land.” Forced evictions to the racially segregated KwaMashu, Umlazi and Chatsworth began. These were strenuously resisted by Cato Manor’s residents, with protest centred on the hated Municipal Beerhalls, symbols of the Apartheid government. These riots, which later became known as the Beerhall Riots, culminated in the mob killing of nine policemen.

In response, Cato Manor was torn down – a community and its history destroyed. Ronnie Govender wrote, “we have built our home, our schools, our temples, our mosques and our churches with love and hard work. It is wrong for the government, in which we have no say, to take from us what is legally ours. This is legalized robbery.”

Even though the area was now a ‘white zone’ it remained a wasteland with scattered Hindu shrines, the foundations of buildings and the occasional fruit tree to remind us of this once vibrant community.

Today

Towards the end of the Apartheid, African and Indian families moved back to Cato Manor, reclaiming their expropriated land. With no clear development policy, the area quickly grew into a shantytown of tin-shacks, shebeens and spaza-shops with many of the problems associated with Cato Manor of the 1950s. Recognizing in Cato Manor an ideal opportunity to redress the wrongs of the past, the city of Durban embarked on an ambitious urban development project, receiving worldwide acclaim as a model for integrated development. The area now boasts low-cost housing, a heritage centre, schools, libraries, community centres and clinics and is home to 90 000 people.

Places to Visit

Cato Manor Heritage Centre

The Heritage Centre is focused on the turbulent history of Cato Manor, using photographic prints of dissent and defiance to illustrate this. Exhibits in the form of news clippings and letters document the evictions and riots that marred the area for decades. The severity of the tone is offset by artwork produced by local artist Joseph Manana, and oral histories read by, amongst others, Jacob Zuma.

Commercial District

Shops, formal and informal, have always been a part of Cato Manor and the area has a rich history of trading by both Indian and African residents. Ronnie Govender describes Mohamed’s Cash Bazaar in At the edge and other Cato Manor Stories:

Every inch of his tiny little shop was taken up with stock even the floor in front of the counter on which stood open hessian bags of rice, mealie meal, dhall, sugar, coarse salt and flour. …Ventilation was bad and when you entered the shop you were assailed by a variety of smells from incense and curry powder to vanilla essence and tobacco, not unpleasant but somewhat overpowering.

The Umkumbaan

The river that gave Cato Manor its Zulu name runs through the centre of the settlement. Ronnie Govender describes its route, “The Umkumbaan cut a swathe through Cato Manor’s lush sub-tropical and market gardens brimming with vegetables, paw-paw, avocado, mango, guava, jack fruit, curry leaf and other exotic plants brought from India in the nineteenth century by indentured labourers.”

Shebeen/Spaza

Shebeens and spaza-shops are part of the Cato Manor landscape. Mostly run by women, these have regulars who, “evening after evening, as soon as they left work, flocked to their favourite shebeens” (Nkosi). These informal establishments are slowly being developed into more conventional bars and shops.

Shacks

Residents of Cato Manor have always had a tradition of building their houses themselves. Even today, areas of Cato Manor consist of tin and wood shacks neighbouring Government built housing:

The tin shanties of Cato Manor clung precariously as if for dear life to the hillsides and slopes overlooking a stream called Mkhumbane, whose greenish slimy waters flowed eastward and southward on its sluggish journey toward the Indian Ocean, embracing to its already heavily polluted bosom all the scum and filth of innumerable shacks without proper sewage, without proper toilets or plumbing, on hot days as unbearable hot as overheated ovens, on rainy days as leaky as sieves ( Nkosi).

Hindu Temples

Hindu temples are scattered throughout Cato Manor and most of them are still in operation today. In Song of the Atman Ronnie Govender describes a festival occurring at the main temple:

Everyone of the children had to observe the Kavadi festival, a punishing ritual of penance undertaken more to propitiate the Gods than to achieve its original aim which way to induce a sense of spirituality in order to achieve liberation from the cycle of birth and death. After the flag-hoisting ceremony at the Cato Manor Temple, the weeks of fasting before the festival were strictly observed. During the festival, hungry and tired in the heat, devotees carried wooden, flower and lime-bedecked Kavadis on their shoulders. The heavier the Kavadis, the more devout you were.

Further Reading

Bhengu, Kenneth. 1958. Ukadebona. Pietermaritzburg: Shuter & Shuter

Hlatshwayo, Mi S’dumo, Temba Alfred Qabula and Nise Malange. 1986. Black Mamba Rising. Durban: Worker Resistance and Culture Publications.

Govender, Kessie. 1976. Working Class Hero.

Govender, Ronnie. 2006. Song of the Atman. Johannesburg: Jacana Media.

________________. 1996. At the edge and other Cato Manor Stories. Pretoria: MANX.

Ngubo, Gladman. 1997. Yekanini Ukuzenza! Cape Town: Kwela Books.

Nkosi, Lewis. 1987. Mating Birds. Johannesburg: Ravan Press.

Compiled by Niall McNulty and Lindy Stiebel.