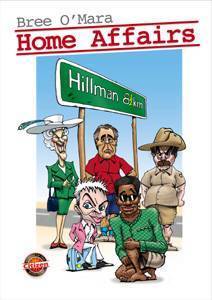

Bree O’Mara

Brigit “Bree” O’Mara (1968-2010) was born in Durban on a Thursday in July, just in time for lunch. Both her parents were Irish. They eloped to South Africa because Bree’s father had passed through Durban during the war and thought the weather was better than the weather in Dublin. Bree started out life in the theatre and performed for all four performing arts councils before the diet of lettuce and watercress became altogether too much to bear. Leaving South Africa as a naive and impressionable girl in 1992 (which was the last time she was either) she went to live in the Middle East, working as the least likely stewardess ever for the national carrier of Bahrain.

She traveled to heaps of countries all over the world and can tell you with some authority that the best public toilets are in Singapore.

After appearing in a television advert for an airline company, the producer got drunk on a flight to London and offered her a job as an Art Director in his film production company. She took the offer (written on a napkin in case he forgot the next day) going on to become the producer of 35mm television commercials and documentaries, writing copies and scripts for both all over the Gulf and Middle Eastern region.

Since then Bree lived and worked in broadcast and print media in Canada, the United States and England. In 2004 Bree became disenchanted with life in the world of media relations (career number three at least if you don’t count a brief stint packing phones for Orange in Oxfordshire) and left the UK for Tanzania, where she lived for a year with the Maasai, working for a small British charity. There she lived with no electricity and no running water and this made her homesick for South Africa. In the course of addressing said homesickness, she journeyed to SA and on the plane met the man who would become her husband. They took up residence in a thatched house in Hartbeesport Dam, in the North West Province, with three dogs, four cats, a plethora of hirsute spiders and a variable electricity and water supply.

Bree spoke a variety of languages, played the harp, detested artichokes and asparagus, followed Formula 1 passionately, and worked in conservation. Having won the coveted Citizen Book Prize in 2007 for her first novel, Home Affairs, she planned to heavily invest in Brabys (whom she believes is actually behind all this name-changing, because with all the upheaval they may as well be printing money!)

She counted Joanne Harris, PJ O’Rourke, Tobias Wolff and Stephen Fry among her favourite authors, although her dirty little secret was a liking for Jonathan Kellerman whodunits.

Bree was due to meet with publishers and sign a contract on her second novel, Nigel Watson, Superhero, when her flight crashed in Libya en route to London. Tragically, she was among the 103 passengers who died in the plane crash on the 12th of May 2010. This second novel was set in London, inspired by her living experiences there during the 1990’s. She was also planning a follow-up to Home Affairs, also to be set in Durban with characters from the previous novel making making return appearances. It remains to be seen whether to be seen whether Nigel Watson, Superhero will be published. An extract is available for reading on breeomara.com.

Website: www.breeomara.com

Publisher: http://www.30degreessouth.co.za/citizen.php?w=7

Extract from Home Affairs (2007).

Repairing to her study, Lady Lambert went to her escritoire and withdrew two sheets of hand-pressed, monogrammed vellum, her Mont Blanc pen and her address book. Now was the time for all good friends to come to her aid in the country…

She sighed. This was going to be so wearisome, this little skirmish, but hopefully with dashed good common sense and a sensible plan it could all be over by dinnertime, or at least in time for the Durban July. In twenty-two years she had never missed out on having a flutter on the gee-gee’s and a few martinis with Dinky and Badger Babcock and all her fun friends, and she wasn’t about to start now because some fatheaded oaf suffering from Foot in Mouth disease wanted to upset the applecart.

She so missed her dear friends in her self-imposed exile, she lamented, but the country air was far more agreeable, the servants much more pliable, and at least she had the July to look forward to. She would also do a little light shopping then (for a new hat, if nothing else), heavy-duty shopping being reserved strictly for London, and take in a lovely opera if one was available. Something jolly, like Wagner, perhaps. God knows they seemed to have abolished all the beautiful arts at The Playhouse lately in favour of gumboot dancing and mass displays of Irish people bouncing around a stage with metal stuck to their shoes. If they couldn’t afford proper footwear they had no business being on a professional stage!

And the plays! Dear God, the positively awful plays! She’d nearly had apoplexy the day she opened the ‘Tonight’ and read a review of something frightful called ‘The Vagina Monologues’. Whatever next! If you couldn’t stage a nice cheerful Hamlet once a year then the whole bally country was disappearing down the drain.

In Tongaat she had been a Patron of the Arts Society and had positively revelled in the role. Of course, Lady Lambert-Lansdowne was no stranger to the performing arts herself, although the full biography of the lady in question was something of a closely guarded secret…

Born in 1927 (a fact which would have been successfully expunged save for the petty bureaucrats who insisted on their ghastly little ID books and passports that were designed to keep the proletariat in check but which were of no good use whatsoever to people of any refinement and class), Lady Eleanor Lambert-Lansdowne had actually started life as Ellen Mavis Perkins -not in Harrow or Belgravia, but in Scunthorpe- in a terraced council house she shared with her mother and her Aunt Maude. At the end of the war (the proper one, not this testy little fracas) she had been eighteen and socially determined, but with little opportunity and even fewer means. She would like to have been able to say that it was the war that had interrupted her dreams of becoming the next Anna Pavlova, but in truth mother Perkins (Mister Perkins having absconded early in Ellen’s childhood) had no disposable capital available for the young Ellen to pursue her lofty ambitions and had encouraged her daughter to join her at the assembly plant where there “was good wages”. Ellen would do no such thing. Blessed with a fine physique and no qualms about putting it on display, Ellen Perkins took to the stage… the stage at the CoCo Club in Soho, where she performed nightly under her professional name, “Ginger”, for gentlemen of varying ages and girths but, more crucially, of consistent wealth. It was there that she met Rupert St.John Lambert-Lansdowne, fifteen years her senior and an ex-Etonian with a very British fondness for crumpet and an insatiable appetite to go with it. Ellen had been a very creative girl in her youth, both on the dance floor and off it, and having seen much of her wares on artistic display in a professional capacity, Rupert decided he’d like to see the rest.

He’d married at the very beginning of the war, while on a furlough, at the insistence of his father who urged him to do the right thing and produce an heir forthwith, just in case the dastardly Huns got the better of their only son while he was over there helping the French overcome their spinelessness. It had been a hasty wedding to Daphne Edwards-Fitzgerald, a homely girl but at least one of suitable stock and appropriate lineage, followed by an even hastier and altogether lacklustre consummation of the nuptials, which produced -to Rupert’s immense relief- no immediate heir. Upon return from the war, having escaped Jerry on the battlefield, Rupert found he enjoyed no such respite from the whinings of a rapacious wife whom he barely knew. The only solution was to take comfort where comfort was offered, namely in the gentlemen’s clubs of Soho, and subsequently in the bespangled arms of ‘Ginger’ Perkins.

Ellen was shrewd, however: while her fellow danseuses were content with a bauble here and a trinket there from the patrons of their little burlesques, Ellen kept her eye on the prize. Although the other girls would give it away for a tennis bracelet or a nice brooch, Ellen drew Rupert out until the poor man was half-crazed with desire. Using her mother’s oft-used adage, she told Rupert that “nobody wanted soiled goods” and said that if he wanted to see the rest of the show, including the reveal, then (somewhat paradoxically) he’d need to make an honest woman of her. And indeed he did.

Mrs. Lambert-Lansdowne the First was summarily dispatched and Ellen Mavis Perkins became Eleanor Lambert-Lansdowne, according to the marriage certificate issued at Marylebone on the 18th of February, 1947. Having unseated the former mistress of the house, Eleanor set about doing a little additional personal housekeeping (which was the last time she did housekeeping of any description) and began by dispensing with her erstwhile accent, wardrobe, family history, and even her family itself. The last Mildred Perkins ever heard of her daughter was a postcard from the Union Castle which read: “Orf to Africa with Rupert, Mummy. Will write. Ta-ta, Eleanor L-L”.

Bibliography

2007. Home Affairs. Johannesburg: 30 Degrees South.

After appearing in a television advert for an airline company, the producer got drunk on a flight to London and offered her a job as an Art Director in his film production company. She took the offer (written on a napkin in case he forgot the next day) going on to become the producer of 35mm television commercials and documentaries, writing copies and scripts for both all over the Gulf and Middle Eastern region.

Since then Bree lived and worked in broadcast and print media in Canada, the United States and England. In 2004 Bree became disenchanted with life in the world of media relations (career number three at least if you don’t count a brief stint packing phones for Orange in Oxfordshire) and left the UK for Tanzania, where she lived for a year with the Maasai, working for a small British charity. There she lived with no electricity and no running water and this made her homesick for South Africa. In the course of addressing said homesickness, she journeyed to SA and on the plane met the man who would become her husband. They took up residence in a thatched house in Hartbeesport Dam, in the North West Province, with three dogs, four cats, a plethora of hirsute spiders and a variable electricity and water supply.

Bree spoke a variety of languages, played the harp, detested artichokes and asparagus, followed Formula 1 passionately, and worked in conservation. Having won the coveted Citizen Book Prize in 2007 for her first novel, Home Affairs, she planned to heavily invest in Brabys (whom she believes is actually behind all this name-changing, because with all the upheaval they may as well be printing money!)

She counted Joanne Harris, PJ O’Rourke, Tobias Wolff and Stephen Fry among her favourite authors, although her dirty little secret was a liking for Jonathan Kellerman whodunits.

Bree was due to meet with publishers and sign a contract on her second novel, Nigel Watson, Superhero, when her flight crashed in Libya en route to London. Tragically, she was among the 103 passengers who died in the plane crash on the 12th of May 2010. This second novel was set in London, inspired by her living experiences there during the 1990’s. She was also planning a follow-up to Home Affairs, also to be set in Durban with characters from the previous novel making making return appearances. It remains to be seen whether to be seen whether Nigel Watson, Superhero will be published. An extract is available for reading on breeomara.com.

Website: www.breeomara.com

Publisher: http://www.30degreessouth.co.za/citizen.php?w=7

Extract from Home Affairs (2007).

Repairing to her study, Lady Lambert went to her escritoire and withdrew two sheets of hand-pressed, monogrammed vellum, her Mont Blanc pen and her address book. Now was the time for all good friends to come to her aid in the country…

She sighed. This was going to be so wearisome, this little skirmish, but hopefully with dashed good common sense and a sensible plan it could all be over by dinnertime, or at least in time for the Durban July. In twenty-two years she had never missed out on having a flutter on the gee-gee’s and a few martinis with Dinky and Badger Babcock and all her fun friends, and she wasn’t about to start now because some fatheaded oaf suffering from Foot in Mouth disease wanted to upset the applecart.

She so missed her dear friends in her self-imposed exile, she lamented, but the country air was far more agreeable, the servants much more pliable, and at least she had the July to look forward to. She would also do a little light shopping then (for a new hat, if nothing else), heavy-duty shopping being reserved strictly for London, and take in a lovely opera if one was available. Something jolly, like Wagner, perhaps. God knows they seemed to have abolished all the beautiful arts at The Playhouse lately in favour of gumboot dancing and mass displays of Irish people bouncing around a stage with metal stuck to their shoes. If they couldn’t afford proper footwear they had no business being on a professional stage!

And the plays! Dear God, the positively awful plays! She’d nearly had apoplexy the day she opened the ‘Tonight’ and read a review of something frightful called ‘The Vagina Monologues’. Whatever next! If you couldn’t stage a nice cheerful Hamlet once a year then the whole bally country was disappearing down the drain.

In Tongaat she had been a Patron of the Arts Society and had positively revelled in the role. Of course, Lady Lambert-Lansdowne was no stranger to the performing arts herself, although the full biography of the lady in question was something of a closely guarded secret…

Born in 1927 (a fact which would have been successfully expunged save for the petty bureaucrats who insisted on their ghastly little ID books and passports that were designed to keep the proletariat in check but which were of no good use whatsoever to people of any refinement and class), Lady Eleanor Lambert-Lansdowne had actually started life as Ellen Mavis Perkins -not in Harrow or Belgravia, but in Scunthorpe- in a terraced council house she shared with her mother and her Aunt Maude. At the end of the war (the proper one, not this testy little fracas) she had been eighteen and socially determined, but with little opportunity and even fewer means. She would like to have been able to say that it was the war that had interrupted her dreams of becoming the next Anna Pavlova, but in truth mother Perkins (Mister Perkins having absconded early in Ellen’s childhood) had no disposable capital available for the young Ellen to pursue her lofty ambitions and had encouraged her daughter to join her at the assembly plant where there “was good wages”. Ellen would do no such thing. Blessed with a fine physique and no qualms about putting it on display, Ellen Perkins took to the stage… the stage at the CoCo Club in Soho, where she performed nightly under her professional name, “Ginger”, for gentlemen of varying ages and girths but, more crucially, of consistent wealth. It was there that she met Rupert St.John Lambert-Lansdowne, fifteen years her senior and an ex-Etonian with a very British fondness for crumpet and an insatiable appetite to go with it. Ellen had been a very creative girl in her youth, both on the dance floor and off it, and having seen much of her wares on artistic display in a professional capacity, Rupert decided he’d like to see the rest.

He’d married at the very beginning of the war, while on a furlough, at the insistence of his father who urged him to do the right thing and produce an heir forthwith, just in case the dastardly Huns got the better of their only son while he was over there helping the French overcome their spinelessness. It had been a hasty wedding to Daphne Edwards-Fitzgerald, a homely girl but at least one of suitable stock and appropriate lineage, followed by an even hastier and altogether lacklustre consummation of the nuptials, which produced -to Rupert’s immense relief- no immediate heir. Upon return from the war, having escaped Jerry on the battlefield, Rupert found he enjoyed no such respite from the whinings of a rapacious wife whom he barely knew. The only solution was to take comfort where comfort was offered, namely in the gentlemen’s clubs of Soho, and subsequently in the bespangled arms of ‘Ginger’ Perkins.

Ellen was shrewd, however: while her fellow danseuses were content with a bauble here and a trinket there from the patrons of their little burlesques, Ellen kept her eye on the prize. Although the other girls would give it away for a tennis bracelet or a nice brooch, Ellen drew Rupert out until the poor man was half-crazed with desire. Using her mother’s oft-used adage, she told Rupert that “nobody wanted soiled goods” and said that if he wanted to see the rest of the show, including the reveal, then (somewhat paradoxically) he’d need to make an honest woman of her. And indeed he did.

Mrs. Lambert-Lansdowne the First was summarily dispatched and Ellen Mavis Perkins became Eleanor Lambert-Lansdowne, according to the marriage certificate issued at Marylebone on the 18th of February, 1947. Having unseated the former mistress of the house, Eleanor set about doing a little additional personal housekeeping (which was the last time she did housekeeping of any description) and began by dispensing with her erstwhile accent, wardrobe, family history, and even her family itself. The last Mildred Perkins ever heard of her daughter was a postcard from the Union Castle which read: “Orf to Africa with Rupert, Mummy. Will write. Ta-ta, Eleanor L-L”.

Bibliography

2007. Home Affairs. Johannesburg: 30 Degrees South.