Bhekisisa Mncube

BHEKISISA MNCUBE was born and raised in the small town of Eshowe, in northern KwaZulu-Natal. He says he was born in South Africa, “black and poor”. His life of poverty propelled him into the political life of the nation. At the penultimate stages of apartheid regime, he served on many anti-apartheid structures, including the African National Congress (ANC). In his adult life, he has been described as a ‘Zulu cultural delinquent’ and ‘part-time darkie’ following his, “jumping off the cliff” stunt to marry a white woman, a one-time ANC activist. He says he is a journalist by profession, but a media relations specialist and writer by vocation.

He has served as a spokesperson to two ANC leaders since 2005. He has been writing and publishing for the last 19 years. He holds a National Diploma as well as a Bachelor of Technology (BTech) degree in Journalism from the Durban University of Technology. He is also a recipient of the coveted Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung International Scholarship (Germany) which funded his journalism studies. He is currently a postgraduate student in the Media and Journalism at the University of Witwatersrand.

His writing has appeared in various publications, including The Witness, Witness/Echo, Sunday Times, Mercury, Sunday Tribune, City Press, Independent on Saturday, Daily News, Sunday World, Politicsweb, Bizcommunity.com and the now defunct – The New Age. Mncube’s memoir, The Love Diary of a Zulu Boy was listed one of the top ten books to read in 2018 by Drum.

Bhekisisa Mncube currently lives in Pretoria, South Africa, and is the director of speechwriting for the minister of basic education. He is an author who has been published at home and abroad. He has written several essays, journal as well as newspaper articles. He has written two books and contributed to several others.

He states: “I write to heal the wounds of the past. As the saying goes, the future is certain; it’s the past that is unpredictable. I believe that writers/authors have a moral responsibility to tell uncomfortable truths about themselves and society. I believe that all lives matter, but there’s a need to pay more attention to the vulnerable bodies of black people. An injustice here remains an injustice everywhere around the world”.

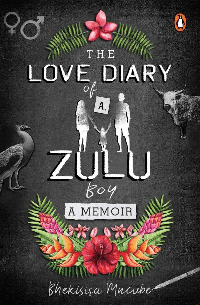

Extract from – The Love Diary of a Zulu Boy (Memoir)

‘Mom, meet my white girlfriend’

It was a historical improbability that my new white girlfriend would be introduced to my family. For three long years, I kept my family in the dark and fed them on manure, like mushrooms, until our daughter was born in 2004. Suddenly, the matter of the official introduction became rather a necessity.

The moment of truth arrived sooner than we imagined. I had prepared my girlfriend for the worst. In my briefing, I told her that my family were very conservative Zulus who swear by the ancestors. I told her that they believed in animal slaughter at the slightest provocation to appease the ancestors. I made it clear that if they decided to slaughter an animal to welcome her, I couldn’t stop them. As you know, my girlfriend has always been averse to killing animals. I disclosed that, politically speaking, we were also at odds, as both my parents belong to the Inkatha Freedom Party. I warned her that my father had threatened to disown us as youngsters if we voted for the ANC.

Now, this titbit about politics was important, as we were both enthusiastic ANC members. I also made it known that I was not quite my father’s favourite son – that we had fallen out in 1993, when I refused to join the police department of the KwaZulu Bantustan government. My father had walked out of his own house after I made it clear that I was headed for Durban to further my tertiary studies. Besides, we had been further estranged since 2006, when my psychologist asked me to ‘kill’ my father to overcome my depression, the malady of the Mncube family. So, I considered myself fatherless. Again, I digress.

Anyway, as a form of insurance, I asked my younger sister to be present at the official white-girlfriend introduction. At least my girlfriend would see a familiar face and have someone to converse with in English. Not only is my girlfriend white, but she speaks no Zulu. This language barrier was huge in that, as a new daughter-in-law, one must make a lasting first impression. How on earth do you make an impression if you can’t khuluma (talk)? At least I didn’t have to worry about her speaking out of turn.

I wasn’t sure how my family would react to seeing a white daughter-in-law. I didn’t know how to prepare them for this eventuality, so I sprang a surprise on them.

In the penultimate stages of our preparations, we had to resolve the issue of the dress code. My father forbids women from wearing pants. In any event, my family tradition dictates that a daughter-in-law has to cover up, including wearing a doek. So I bought her a stylish, Xhosa-inspired dress that covered everything, as my parents preferred, but she refused to wear a doek to cover her hair.

We arrived, as planned, on a Saturday afternoon. We alighted from the car, a familiar-looking woman emerging, holding a baby. Surprise number one: she was white. Surprise number two: she was known to my family as an academic who had taught my late brother. She had, on two occasions, seen both my parents in the flesh – at my brother’s funeral, and at the awarding of his posthumous honours degree. Surprise number three: there was a baby. My daughter was six weeks old at the time.

We started to approach the family homestead, my mother and other family members standing outside one of the huts to welcome us. From my vantage point, I could discern a sense of both disbelief and sheer wonder. But there was still tension in the air – unsurprising, given the magnitude of the occasion. My mother blurted out words of joy. She ululated, sang and danced, as she is wont to do when exciting events occur. But she was the only happy chappy in the whole group. She even managed to hold our daughter in her arms; in the picture, though, it looks like she is in a precarious position. To this day, my daughter complains that my mother was holding her like a pocket of potatoes.

My father stood there motionless, looking perplexed. My other siblings still had to process the atmosphere, so their faces were expressionless. This was new to all of us. I had brought a white woman into a black Zulu family. I am told my grandparents had had run-ins with white people during colonial times. Possibly, some ancestors had died believing that white people were their enemies. Who could blame them? But, she is here now – holding out the hand of friendship and saying she wants to join this Zulu family. The whole scene resembled a speed session of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. In a split second, my girlfriend had to make an imaginary confession before my family that she had no apartheid skeletons in her closet so that she could receive an instant pardon. In retrospect, I think she did receive an instant pardon. There were more words spoken in those silent moments than have been uttered since. As the shock of the moment subsided, we were ushered into the family home.

But not before my father caused a drama to unfold. You see, for many years my father boasted that he spoke better English than the rest of us educated children. We all expected my father to make good on his promise and speak his better English to my white girlfriend. Without any prior discussions, all my siblings were awaiting my father’s bombshell. It came; he didn’t disappoint. He looked my girlfriend in the eye and said, in some funny language later believed to be Fanakalo (a workplace lingua franca in South Africa for over a hundred years): ‘We na thanda lakhaya,’ loosely translated to mean: ‘You love somebody in this household.’ In unison, we burst out laughing until we cried tears of joy. My girlfriend was unperturbed by our laughter as my father continued: ‘Mina cela imali khismuzi,’ loosely translated as ‘May I have money for Christmas.’ Although it was early December, my father had the whole Christmas theme running at full speed. We launched into a second frenzy of laughter, and I am sure someone was rolling on the floor. Our day was made. Most importantly, my father had broken the ice. My girlfriend stood there, grinning from ear to ear. She understood nothing and probably wished the whole circus would leave town soon, longing for a moment of silence to reflect on her new journey into the world of the unknown.

Reviews of The Love Diary of a Zulu Boy

The life of Zulu journalist Bhekisisa Mncube – from his upbringing and painful relationship with his father through the years of his pre-marital sexual encounters and his later marriage to an Englishwoman–is rendered with humour and self-reflection. In the process, Mncube evokes the spectrum of traditional Zulu culture: after much contemplation, he performs the expected sacred spiritual rituals which his parents believe will bless his marriage. In support of everything Mncube has experienced, he learns to apologise for his wrongs, and honoring these life lessons results in a deliverance of himself as a “dependable father, husband and human being” (Mncube, 2018, pg.204). This memoir is rich with memories and cultural experiences that unveil the pleasures and challenges of the author trying to understand himself as a Zulu boy in modern day South Africa.

Jozi’s Books and Blogs Festival.

The Love Diary of a Zulu Boy – Funny, charming and captivating, this memoir of interracial love is a heart-warming story of an unconventional love affair. Zulu boy, Bhekisisa Mncube, escapes the suffocating small-town vibes of his village for bigger things in Durban. He finds himself moving in with a white academic, who he refers to only as Professor D. True love follows, and we are entertained and charmed by the cultural hoops through which he has to jump to win approval on both sides.

Love Books, Johannesburg.

I loved the rich descriptions and interpretations of Zulu culture as relayed by Mncube and I learnt lots of things I previously had only a vague understanding of, for instance, the rituals, the prayers to the ancestors and the reasons for the slaying of various animals, which Professor D. abhors because she is a vegetarian. The book also deals with very serious subjects, ranging from sexual abuse, the minefield of family politics and dynamics, the way men use women, the struggle, mental health issues and others. There are no sacred cows. Broken into easily digestible chapters, each a separate story, it is a perfect dip-into-whenever-you-can read. This brilliant memoir crosses spoken and unspoken barriers in our country, laying bare the elephant in the room, weaving between time and cultural space, holding the promise of great fascination until the last page.

Ms Stephanie Saville, Witness Deputy Editor.

This romantic memoir is written by a talented journalist Bhekisisa Mncube – where he delves into interracial relationships and the discriminations thereafter. The Love Diary of a Zulu Boy zooms into the author’s imagination about marrying across colour lines eight years before he even met his wife, who he refers to as Professor D. This may be Bhekisisa’s debut book but it’s written with such intelligence and wit. Even though his story is about serious struggles faced by couples in interracial relationships, you can also sense the author’s humour when he speaks about his wife’s blackness, or rather his whiteness.

Ms Khosi Biyela, W24

The book is an honest meditation of a black man growing up in a racist country, marrying across the racial line, and then suddenly waking up startled by what he has done. The young man is wondering if what he has done is an act of ethnic betrayal, or an affirmation of a shared humanity. There’s a visceral convergence here between the personal and the political, a search for belonging, but also a quest for truth about what it means to be human in a country that has always relegated one’s human essence to the backburner, while it put on the pedestal one’s racial or ethnic affiliation. We need books that entertain while they teach, that offend while they affirm, that comfort while they question, and The Love Diary of a Zulu Boy fits the bill.

–Fred Khumalo, seasoned journalist, and author of six books including the Dancing the Death Drill.

Bibliography

2019. Thokozani, Kumnandi Emakhaya. Macmillan Education: South Africa.

December 2018. Opposites attract… trouble: Seventy years after interracial marriages were prohibited in South Africa, the author writes about what happened when he married a white woman. Global quarterly, Index on Censorship magazine, UK.

2018. The Love Diary of a Zulu Boy (A Memoir), Penguin Random House South Africa.

2014. FET First English Level 4 Student’s Book, Macmillan South Africa (Contributor).

2011. Love in the Times of AIDS. New Agenda South African journal of social and economic policy. Also published in the Witness (RSA) and EzineArticles.com: A Peer-Reviewed Articles & Marketing Writers’ ejournal (USA), (Contributor – Academic Book Review).

2005. ‘A Critical Engagement with Society,’ Book Chapters: The University of KwaZulu-Natal (Contributor).

2005. ‘Yesterday’. Passages: A Chronicle of the African Humanities, University of Michigan Library (USA) (Contributor – Movie Review).

His writing has appeared in various publications, including The Witness, Witness/Echo, Sunday Times, Mercury, Sunday Tribune, City Press, Independent on Saturday, Daily News, Sunday World, Politicsweb, Bizcommunity.com and the now defunct – The New Age. Mncube’s memoir, The Love Diary of a Zulu Boy was listed one of the top ten books to read in 2018 by Drum.

Bhekisisa Mncube currently lives in Pretoria, South Africa, and is the director of speechwriting for the minister of basic education. He is an author who has been published at home and abroad. He has written several essays, journal as well as newspaper articles. He has written two books and contributed to several others.

He states: “I write to heal the wounds of the past. As the saying goes, the future is certain; it’s the past that is unpredictable. I believe that writers/authors have a moral responsibility to tell uncomfortable truths about themselves and society. I believe that all lives matter, but there’s a need to pay more attention to the vulnerable bodies of black people. An injustice here remains an injustice everywhere around the world”.

Extract from – The Love Diary of a Zulu Boy (Memoir)

‘Mom, meet my white girlfriend’

It was a historical improbability that my new white girlfriend would be introduced to my family. For three long years, I kept my family in the dark and fed them on manure, like mushrooms, until our daughter was born in 2004. Suddenly, the matter of the official introduction became rather a necessity.

The moment of truth arrived sooner than we imagined. I had prepared my girlfriend for the worst. In my briefing, I told her that my family were very conservative Zulus who swear by the ancestors. I told her that they believed in animal slaughter at the slightest provocation to appease the ancestors. I made it clear that if they decided to slaughter an animal to welcome her, I couldn’t stop them. As you know, my girlfriend has always been averse to killing animals. I disclosed that, politically speaking, we were also at odds, as both my parents belong to the Inkatha Freedom Party. I warned her that my father had threatened to disown us as youngsters if we voted for the ANC.

Now, this titbit about politics was important, as we were both enthusiastic ANC members. I also made it known that I was not quite my father’s favourite son – that we had fallen out in 1993, when I refused to join the police department of the KwaZulu Bantustan government. My father had walked out of his own house after I made it clear that I was headed for Durban to further my tertiary studies. Besides, we had been further estranged since 2006, when my psychologist asked me to ‘kill’ my father to overcome my depression, the malady of the Mncube family. So, I considered myself fatherless. Again, I digress.

Anyway, as a form of insurance, I asked my younger sister to be present at the official white-girlfriend introduction. At least my girlfriend would see a familiar face and have someone to converse with in English. Not only is my girlfriend white, but she speaks no Zulu. This language barrier was huge in that, as a new daughter-in-law, one must make a lasting first impression. How on earth do you make an impression if you can’t khuluma (talk)? At least I didn’t have to worry about her speaking out of turn.

I wasn’t sure how my family would react to seeing a white daughter-in-law. I didn’t know how to prepare them for this eventuality, so I sprang a surprise on them.

In the penultimate stages of our preparations, we had to resolve the issue of the dress code. My father forbids women from wearing pants. In any event, my family tradition dictates that a daughter-in-law has to cover up, including wearing a doek. So I bought her a stylish, Xhosa-inspired dress that covered everything, as my parents preferred, but she refused to wear a doek to cover her hair.

We arrived, as planned, on a Saturday afternoon. We alighted from the car, a familiar-looking woman emerging, holding a baby. Surprise number one: she was white. Surprise number two: she was known to my family as an academic who had taught my late brother. She had, on two occasions, seen both my parents in the flesh – at my brother’s funeral, and at the awarding of his posthumous honours degree. Surprise number three: there was a baby. My daughter was six weeks old at the time.

We started to approach the family homestead, my mother and other family members standing outside one of the huts to welcome us. From my vantage point, I could discern a sense of both disbelief and sheer wonder. But there was still tension in the air – unsurprising, given the magnitude of the occasion. My mother blurted out words of joy. She ululated, sang and danced, as she is wont to do when exciting events occur. But she was the only happy chappy in the whole group. She even managed to hold our daughter in her arms; in the picture, though, it looks like she is in a precarious position. To this day, my daughter complains that my mother was holding her like a pocket of potatoes.

My father stood there motionless, looking perplexed. My other siblings still had to process the atmosphere, so their faces were expressionless. This was new to all of us. I had brought a white woman into a black Zulu family. I am told my grandparents had had run-ins with white people during colonial times. Possibly, some ancestors had died believing that white people were their enemies. Who could blame them? But, she is here now – holding out the hand of friendship and saying she wants to join this Zulu family. The whole scene resembled a speed session of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. In a split second, my girlfriend had to make an imaginary confession before my family that she had no apartheid skeletons in her closet so that she could receive an instant pardon. In retrospect, I think she did receive an instant pardon. There were more words spoken in those silent moments than have been uttered since. As the shock of the moment subsided, we were ushered into the family home.

But not before my father caused a drama to unfold. You see, for many years my father boasted that he spoke better English than the rest of us educated children. We all expected my father to make good on his promise and speak his better English to my white girlfriend. Without any prior discussions, all my siblings were awaiting my father’s bombshell. It came; he didn’t disappoint. He looked my girlfriend in the eye and said, in some funny language later believed to be Fanakalo (a workplace lingua franca in South Africa for over a hundred years): ‘We na thanda lakhaya,’ loosely translated to mean: ‘You love somebody in this household.’ In unison, we burst out laughing until we cried tears of joy. My girlfriend was unperturbed by our laughter as my father continued: ‘Mina cela imali khismuzi,’ loosely translated as ‘May I have money for Christmas.’ Although it was early December, my father had the whole Christmas theme running at full speed. We launched into a second frenzy of laughter, and I am sure someone was rolling on the floor. Our day was made. Most importantly, my father had broken the ice. My girlfriend stood there, grinning from ear to ear. She understood nothing and probably wished the whole circus would leave town soon, longing for a moment of silence to reflect on her new journey into the world of the unknown.

Reviews of The Love Diary of a Zulu Boy

The life of Zulu journalist Bhekisisa Mncube – from his upbringing and painful relationship with his father through the years of his pre-marital sexual encounters and his later marriage to an Englishwoman–is rendered with humour and self-reflection. In the process, Mncube evokes the spectrum of traditional Zulu culture: after much contemplation, he performs the expected sacred spiritual rituals which his parents believe will bless his marriage. In support of everything Mncube has experienced, he learns to apologise for his wrongs, and honoring these life lessons results in a deliverance of himself as a “dependable father, husband and human being” (Mncube, 2018, pg.204). This memoir is rich with memories and cultural experiences that unveil the pleasures and challenges of the author trying to understand himself as a Zulu boy in modern day South Africa.

Jozi’s Books and Blogs Festival.

The Love Diary of a Zulu Boy – Funny, charming and captivating, this memoir of interracial love is a heart-warming story of an unconventional love affair. Zulu boy, Bhekisisa Mncube, escapes the suffocating small-town vibes of his village for bigger things in Durban. He finds himself moving in with a white academic, who he refers to only as Professor D. True love follows, and we are entertained and charmed by the cultural hoops through which he has to jump to win approval on both sides.

Love Books, Johannesburg.

I loved the rich descriptions and interpretations of Zulu culture as relayed by Mncube and I learnt lots of things I previously had only a vague understanding of, for instance, the rituals, the prayers to the ancestors and the reasons for the slaying of various animals, which Professor D. abhors because she is a vegetarian. The book also deals with very serious subjects, ranging from sexual abuse, the minefield of family politics and dynamics, the way men use women, the struggle, mental health issues and others. There are no sacred cows. Broken into easily digestible chapters, each a separate story, it is a perfect dip-into-whenever-you-can read. This brilliant memoir crosses spoken and unspoken barriers in our country, laying bare the elephant in the room, weaving between time and cultural space, holding the promise of great fascination until the last page.

Ms Stephanie Saville, Witness Deputy Editor.

This romantic memoir is written by a talented journalist Bhekisisa Mncube – where he delves into interracial relationships and the discriminations thereafter. The Love Diary of a Zulu Boy zooms into the author’s imagination about marrying across colour lines eight years before he even met his wife, who he refers to as Professor D. This may be Bhekisisa’s debut book but it’s written with such intelligence and wit. Even though his story is about serious struggles faced by couples in interracial relationships, you can also sense the author’s humour when he speaks about his wife’s blackness, or rather his whiteness.

Ms Khosi Biyela, W24

The book is an honest meditation of a black man growing up in a racist country, marrying across the racial line, and then suddenly waking up startled by what he has done. The young man is wondering if what he has done is an act of ethnic betrayal, or an affirmation of a shared humanity. There’s a visceral convergence here between the personal and the political, a search for belonging, but also a quest for truth about what it means to be human in a country that has always relegated one’s human essence to the backburner, while it put on the pedestal one’s racial or ethnic affiliation. We need books that entertain while they teach, that offend while they affirm, that comfort while they question, and The Love Diary of a Zulu Boy fits the bill.

–Fred Khumalo, seasoned journalist, and author of six books including the Dancing the Death Drill.

Bibliography

2019. Thokozani, Kumnandi Emakhaya. Macmillan Education: South Africa.

December 2018. Opposites attract… trouble: Seventy years after interracial marriages were prohibited in South Africa, the author writes about what happened when he married a white woman. Global quarterly, Index on Censorship magazine, UK.

2018. The Love Diary of a Zulu Boy (A Memoir), Penguin Random House South Africa.

2014. FET First English Level 4 Student’s Book, Macmillan South Africa (Contributor).

2011. Love in the Times of AIDS. New Agenda South African journal of social and economic policy. Also published in the Witness (RSA) and EzineArticles.com: A Peer-Reviewed Articles & Marketing Writers’ ejournal (USA), (Contributor – Academic Book Review).

2005. ‘A Critical Engagement with Society,’ Book Chapters: The University of KwaZulu-Natal (Contributor).

2005. ‘Yesterday’. Passages: A Chronicle of the African Humanities, University of Michigan Library (USA) (Contributor – Movie Review).