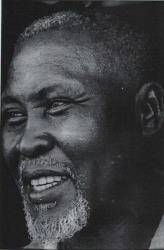

Albert Luthuli

Albert John Luthuli (1898 – 1967), also known by his Zulu name Mvumbi, was a South African teacher and politician. Luthuli was elected president of the African National Congress (ANC), at the time an umbrella organisation that led opposition to the white minority government in South Africa. He was awarded the 1960 Nobel Peace Prize for his role in the non-violent struggle against apartheid. He was the first African, and the first person from outside Europe and the Americas, to be awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. The third son of Seventh-day Adventist missionary John Bunyan Luthuli and Mtonya Gumede, Albert Luthuli was born near Bulawayo in what was then called Rhodesia, around 1898.

His father died, and he and his mother returned to her ancestral home of Groutville in KwaDukuza (Stanger), Natal, South Africa. He stayed with his uncle, Martin Luthuli, who was at that time the elected chief of the Christian Zulus inhabiting the Umzinyathi District Municipality mission Reserve.

On completing a teaching course at Edendale, near Pietermaritzburg, Lutuli accepted the post of principal and only teacher at a primary school in rural Blaauwbosch, Newcastle, Natal. Here Luthuli was confirmed in the Methodist Church and became a lay preacher. In 1920 he received a government bursary to attend a higher teachers’ training course at Adams College, and subsequently joined the training college staff, teaching alongside Z.K. Mathews, who was then head of the Adams College High School. To provide financial support for his mother, he declined a scholarship to the University of Fort Hare.

In 1928 he became secretary of the African Teacher’s Association and in 1933 its president. He was also active in missionary work. In 1933 the tribal elders asked Luthuli to become chief of the tribe. For two years he hesitated, but accepted the call in early 1936 and became chieftain, until removed from this office by the government in 1952.

In 1936 the government disenfranchised the only black Africans who had had voting rights — those in Cape Province. In 1948 the Nationalist Party, which was in control of the government, adopted the policy of apartheid (apartness) and over the next decade the Pass Laws were tightened. In 1944 Luthuli joined the African National Congress (ANC) and in 1945 he was elected to the Committee of the KwaZulu Province Provincial Division of ANC and in 1951 to the presidency of the Division. The next year he joined with other ANC leaders in organizing nonviolent campaigns to defy discriminatory laws.

The government, charging Luthuli with a conflict of interest, demanded that he withdraw his membership in ANC or forfeit his office as tribal chief. Refusing to do either, he was dismissed from his chieftainship.

A month later Luthuli was elected president-general of ANC, formally nominated by the future Pan Africanist Congress leader Potlako Leballo. Responding immediately, the government imposed two two-year bans on Luthuli’s movement. When the second ban expired in 1956, he attended an ANC conference only to be arrested and charged with treason a few months later, along with 155 others. In December 1957, after nearly a year in custody during the preliminary hearings, Luthuli was released and the charges against him and sixty-four of his compatriots were dropped.

Another five year ban confined him to a fifteen-mile radius of his home. The ban was temporarily lifted while he testified at the continuing treason trials. It was lifted again in March 1960, to permit his arrest for publicly burning his pass following the Sharpeville massacre. In the ensuing state of emergency he was arrested, found guilty, fined, given a suspended jail sentence and returned to Groutville. One final time the ban was lifted, this time for ten days in early December 1961 to permit Luthuli and his wife to attend the Nobel Peace Prize ceremonies in Oslo, an award described by Die Transvaler as “an inexplicable pathological phenomenon”.

Luthuli’s leadership of the ANC covered the period of violent disputes between the party’s “Africanist” and “Charterist” wings. Africanist critics claim Luthuli was peripherialized in Natal and the Transvaal ANC Provincial branch and its Communist Party (CPSA officially dissolved 1950 but secretly reconstituted 1953 as SACP) allies took advantage of this situation. Luthuli did not see the Freedom Charter before it was adopted by acclaim at Kliptown in 1955. After reading the document and realising the ANC, despite its numerical superiority, had been subordinated to one vote in a five member multiracial and trade union “Congress Alliance”, Luthuli rejected the Charter but then later accepted it partly to counter the more radical Africanist wing whom he likened to black nazis. In 1959 the Africanists split from the ANC over the issue of the Freedom Charter and Oliver Tambo’s 1958 rewriting of the ANC Constitution, founding the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC). The PAC posed a serious challenge to the ANC until its military wing was destroyed at Itumbi camp, Chunya, Tanzania in March 1980.

In December 1961, without Luthuli’s sanction, Nelson Mandela of the Provincial ANC publicly launched Umkhonto we Sizwe at the All In Conference, where delegates from several movements had convened to discuss cooperation. Mandela’s charisma and the global publicity surrounding his trial and imprisonment upstaged Luthuli, who grew increasingly despondent in isolation. (In Mandela’s autobiography, he insists that Luthuli was consulted and consented before the formation of Umkhonto we Sizwe.)

In 1962 he was elected Rector of the University of Glasgow by the students, serving until 1965. Since he was banned from travelling to Glasgow the Luthuli Scholarship Fund was setup by the Student Representative Council to enable a black South African student to study at Glasgow University. Later that year he published an autobiography titled Let My People Go. This was the only book he authored but Luthuli also wrote many articles and speeches.

A fourth ban to run for five years confining Luthuli to the immediate vicinity of his home was issued in May 1964, to run concurrently with the third ban. In 1966, he was visited by United States Senator Robert F. Kennedy, who was visiting South Africa at the time. The two discussed the ANC’s struggle. Senator Kennedy’s visit to the country, and his meeting with Luthuli in particular, caused an increase of world awareness of the plight of black South Africans. In July 1967, at the age of 69, he was fatally injured in an accident near his home in Stanger.

Extract from Let My People Go

At about the time when the Battle of Waterloo brought an end to the turbulent and disruptive career of Emperor Napoleon, a man of similar ambition came to power in a far off and little known Zululand. In a brief twelve year reign, Shaka, undoubtedly the greatest of the Zulu kinds, welded a number of bickering clans into a strong united nation.

Shaka achieved the feat of creating the Zulu nation by methods which were sometimes ruthless. All the same, his occasional ruthlessness was minor by comparison with that of modern dictators, and it was seldom, if ever, as calculated and sub-human as theirs.

Shaka has been much maligned by white South African historians. His outlook was that of his day, and when that is taken into account, and when all that can be said to his discredit has been said, this king of legendary physique emerges as a brilliant general, and a ruler of great courage, intelligence and ability. Without the moral support of any precedent, has had the strength to withstand (and on occasion to expose) the power exerted over his people by wizards. His reorganisation of his army was enough to make it in his time the mightiest military force in Africa.

Nevertheless, Shaka did violate some of the customs of his people, and this was his undoing. In particular, he over-used his army, allowing his soldiers little time for the normal pursuits of peace. As the years passed, his ambitions got the better of him. That he could be despotic was probably no great matter, but his people expected their king to temper this with benevolence. Shaka’s rule grew harsher. Finally, he estranged himself from his people by setting up as an unqualified dictator. For a time, his subjects submitted to arbitrary rule as loyally as they could. In the end, however, Shaka went the way of most tyrants. Even his army appears to have connived at his assassination by his half-brother Dingane. The extent to which he had forfeited the allegiance of his subjects is seen in that no murmur was raised against his assassins. Shaka died unmourned by the nations which he had raised out of obscurity.

Bibliography

1962. Let My People Go. Cape Town: David Krut Publishers.

On completing a teaching course at Edendale, near Pietermaritzburg, Lutuli accepted the post of principal and only teacher at a primary school in rural Blaauwbosch, Newcastle, Natal. Here Luthuli was confirmed in the Methodist Church and became a lay preacher. In 1920 he received a government bursary to attend a higher teachers’ training course at Adams College, and subsequently joined the training college staff, teaching alongside Z.K. Mathews, who was then head of the Adams College High School. To provide financial support for his mother, he declined a scholarship to the University of Fort Hare.

In 1928 he became secretary of the African Teacher’s Association and in 1933 its president. He was also active in missionary work. In 1933 the tribal elders asked Luthuli to become chief of the tribe. For two years he hesitated, but accepted the call in early 1936 and became chieftain, until removed from this office by the government in 1952.

In 1936 the government disenfranchised the only black Africans who had had voting rights — those in Cape Province. In 1948 the Nationalist Party, which was in control of the government, adopted the policy of apartheid (apartness) and over the next decade the Pass Laws were tightened. In 1944 Luthuli joined the African National Congress (ANC) and in 1945 he was elected to the Committee of the KwaZulu Province Provincial Division of ANC and in 1951 to the presidency of the Division. The next year he joined with other ANC leaders in organizing nonviolent campaigns to defy discriminatory laws.

The government, charging Luthuli with a conflict of interest, demanded that he withdraw his membership in ANC or forfeit his office as tribal chief. Refusing to do either, he was dismissed from his chieftainship.

A month later Luthuli was elected president-general of ANC, formally nominated by the future Pan Africanist Congress leader Potlako Leballo. Responding immediately, the government imposed two two-year bans on Luthuli’s movement. When the second ban expired in 1956, he attended an ANC conference only to be arrested and charged with treason a few months later, along with 155 others. In December 1957, after nearly a year in custody during the preliminary hearings, Luthuli was released and the charges against him and sixty-four of his compatriots were dropped.

Another five year ban confined him to a fifteen-mile radius of his home. The ban was temporarily lifted while he testified at the continuing treason trials. It was lifted again in March 1960, to permit his arrest for publicly burning his pass following the Sharpeville massacre. In the ensuing state of emergency he was arrested, found guilty, fined, given a suspended jail sentence and returned to Groutville. One final time the ban was lifted, this time for ten days in early December 1961 to permit Luthuli and his wife to attend the Nobel Peace Prize ceremonies in Oslo, an award described by Die Transvaler as “an inexplicable pathological phenomenon”.

Luthuli’s leadership of the ANC covered the period of violent disputes between the party’s “Africanist” and “Charterist” wings. Africanist critics claim Luthuli was peripherialized in Natal and the Transvaal ANC Provincial branch and its Communist Party (CPSA officially dissolved 1950 but secretly reconstituted 1953 as SACP) allies took advantage of this situation. Luthuli did not see the Freedom Charter before it was adopted by acclaim at Kliptown in 1955. After reading the document and realising the ANC, despite its numerical superiority, had been subordinated to one vote in a five member multiracial and trade union “Congress Alliance”, Luthuli rejected the Charter but then later accepted it partly to counter the more radical Africanist wing whom he likened to black nazis. In 1959 the Africanists split from the ANC over the issue of the Freedom Charter and Oliver Tambo’s 1958 rewriting of the ANC Constitution, founding the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC). The PAC posed a serious challenge to the ANC until its military wing was destroyed at Itumbi camp, Chunya, Tanzania in March 1980.

In December 1961, without Luthuli’s sanction, Nelson Mandela of the Provincial ANC publicly launched Umkhonto we Sizwe at the All In Conference, where delegates from several movements had convened to discuss cooperation. Mandela’s charisma and the global publicity surrounding his trial and imprisonment upstaged Luthuli, who grew increasingly despondent in isolation. (In Mandela’s autobiography, he insists that Luthuli was consulted and consented before the formation of Umkhonto we Sizwe.)

In 1962 he was elected Rector of the University of Glasgow by the students, serving until 1965. Since he was banned from travelling to Glasgow the Luthuli Scholarship Fund was setup by the Student Representative Council to enable a black South African student to study at Glasgow University. Later that year he published an autobiography titled Let My People Go. This was the only book he authored but Luthuli also wrote many articles and speeches.

A fourth ban to run for five years confining Luthuli to the immediate vicinity of his home was issued in May 1964, to run concurrently with the third ban. In 1966, he was visited by United States Senator Robert F. Kennedy, who was visiting South Africa at the time. The two discussed the ANC’s struggle. Senator Kennedy’s visit to the country, and his meeting with Luthuli in particular, caused an increase of world awareness of the plight of black South Africans. In July 1967, at the age of 69, he was fatally injured in an accident near his home in Stanger.

Extract from Let My People Go

At about the time when the Battle of Waterloo brought an end to the turbulent and disruptive career of Emperor Napoleon, a man of similar ambition came to power in a far off and little known Zululand. In a brief twelve year reign, Shaka, undoubtedly the greatest of the Zulu kinds, welded a number of bickering clans into a strong united nation.

Shaka achieved the feat of creating the Zulu nation by methods which were sometimes ruthless. All the same, his occasional ruthlessness was minor by comparison with that of modern dictators, and it was seldom, if ever, as calculated and sub-human as theirs.

Shaka has been much maligned by white South African historians. His outlook was that of his day, and when that is taken into account, and when all that can be said to his discredit has been said, this king of legendary physique emerges as a brilliant general, and a ruler of great courage, intelligence and ability. Without the moral support of any precedent, has had the strength to withstand (and on occasion to expose) the power exerted over his people by wizards. His reorganisation of his army was enough to make it in his time the mightiest military force in Africa.

Nevertheless, Shaka did violate some of the customs of his people, and this was his undoing. In particular, he over-used his army, allowing his soldiers little time for the normal pursuits of peace. As the years passed, his ambitions got the better of him. That he could be despotic was probably no great matter, but his people expected their king to temper this with benevolence. Shaka’s rule grew harsher. Finally, he estranged himself from his people by setting up as an unqualified dictator. For a time, his subjects submitted to arbitrary rule as loyally as they could. In the end, however, Shaka went the way of most tyrants. Even his army appears to have connived at his assassination by his half-brother Dingane. The extent to which he had forfeited the allegiance of his subjects is seen in that no murmur was raised against his assassins. Shaka died unmourned by the nations which he had raised out of obscurity.

Bibliography

1962. Let My People Go. Cape Town: David Krut Publishers.